By Mike Allen

Photographs by Brandon Clower

While finishing my Christmas shopping last year, I fell madly in love with a greeting card. I wasn’t necessarily planning to buy greeting cards, since, in my experience, no one really cherishes bought greeting cards. Like animatronic polar bears and tinsel, they persist despite their hideously obvious insincerity. But tradition dictates that greeting cards mean more than gifts, for they are the redeeming veneer of sentiment (the thought) concealing the vulgar thrill of exchanging junk (that counts) for love.

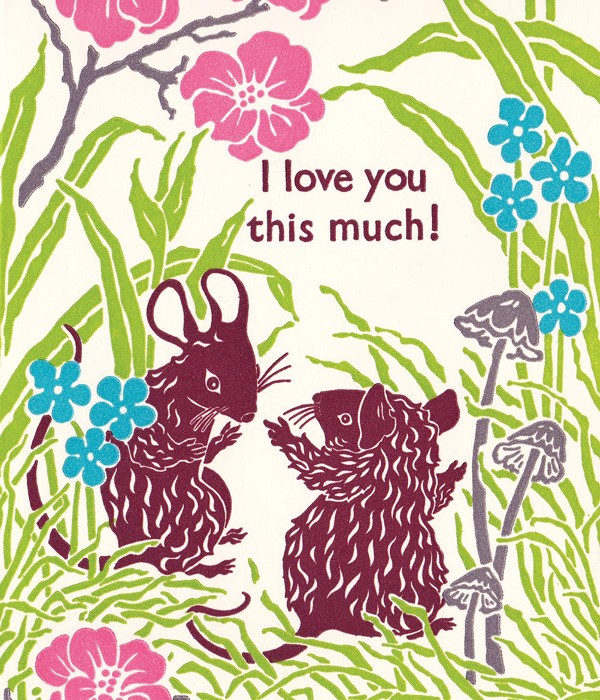

I was at the Red Sail store on Alberta. I approached a back-wall display of greeting cards and locked eyes on one in particular, and every other faded away. Earth tones on matte card stock depicted two brown mice amongst a miniature landscape of grasses, flowers, and mushrooms. One mouse, quite chubby, faces the Other, more slender, mouse holding his arms wide. “I love you this much!” reads the caption. I was captivated. What are those? Flowering Quince? Those mushrooms, some type of Mycena or Marasmius species? I was sure my wife and I had marveled at them on some long-ago foraging expedition. And the caption! My daughter had lately been in the habit of the same expression.

I didn’t need to look any further. I couldn’t look any further. I picked it up, and turned it over: $7.

I had been boutique shopping. I had just spent several dollars more than necessary on perhaps a dozen other items. Vintage ladies’ handkerchiefs for $5 each; tiny, inconsequential toy stocking stuffers $6, $7, $8… it was beginning to take its toll. I balked and set the card back on its clear plastic shelf. I tried to look around, but in vain; my gaze always fell back on the same object, my mind having noted nothing else of interest.

I picked it up again and read the little slip inserted into back: Hand-drawn design, hand printed on an old letterpress in Portland, Oregon. Well, isn’t that just too perfectly fucking precious? It was like a (non?)ironic summary of Portland boutique ethos. What’s a normal card cost, $3.50 or so? I supposed I could just buy one card for both wife and child.

Of course we spent Christmas eve drinking Seelbach cocktails late into the night, having wisely wrapped the child’s presents in the preceding nights. So I had to fill out the card in the morning, after all the presents had been opened, furtively scrawling the most heartfelt declarations I could muster from the champagne and bourbon sponge behind my eyes. It seemed a sin to get my acetylaldehyde-stinking morning sweat on the precious card stock, so I kept it short and sealed it without addressing it. My wife opened it and, without a word, I could tell she felt the same way I did.

“You like it?” I asked, still slightly tentative.

“Oh my god, I almost teared up,” she said.

“I’m gonna write a story about this card,” I said excitedly.

“Who made it?”

“Oh, some people with an antique letterpress, here in Portland.”

“Of course,” she said.

We had a good laugh at that.

Letterpress, I thought, that’s like a fancy card printer, right?

I lost the little insert in the package that explained who made the thing, and how. My wife pointed out the embossed logo at the bottom of the back.

Reed’s work is consistently folksy but occasionally verges on psychedelia as in, for example, his ’60s era camping motifs. In my favorite, (Dr.) Seussian coniferous trees adorned with oversized cones, surround a family of three gathered around a campfire. Above, a few Dijon-yellow impressions suggesting a night sky defy the negative space that yells daylight. I read it as a folksy allusion to gold gilt that serves to lift the muted earth tones of the arboreal. The fine details are saved for the National Forest-brown in which the family is impressed. It succeeds in recalling a childhood of mythological idyll. Were this a freehand work in a gallery, I’d expect snide irony masquerading as identity politics. But here, the method of production is more important than the greeting card’s raison d’etre in discerning the sincerity of the sentiment.

Old School Stationers is one Brian Reed, who operates three large and dangerous-looking pieces of machinery in the basement of the Ford building, on the same concrete floor where Model T’s were once assembled. Brian’s main machine, a Chandler and Price (C&P) 10 x 15 old-series platen press, was built before the Model T was invented.

Serpentine spokes adorn a massive flywheel, belt-driven by a three-quarter horsepower motor bolted to the floor. Opposite that, two massive gears provide torque to an almost comically Victorian system of pistons, cams, arms, rods, rollers &c. The printer (the human being) stands between these mechanical primitives at an elegant wooden workspace; it even has a little swing table, called a feed table, for extra room. When in motion, the rhythm is complex, hypnotic.

Letterpress, as it turns out, isn’t just a fancy way of saying printing. The letterpress technique seems the most obvious way to transfer a pattern of ink to paper, as it simply means that the ink is applied to raised type or engraved plates, and the type is then pressed onto the paper. Johannes Gutenberg’s movable type press—the one that, as you learned in school, changed the way media was disseminated even more radically than the Internet—was a letterpress. Then we have Gravure printing, which predates Gutenberg by a century or more and involves etching the image into metal, filling the recessed areas with ink, and pressing the paper into the recessed area. High-quality imagery (magazines, packaging) is still mass-produced using gravure-engraved rollers. Then there’s lithography, the most ubiquitous technique for high-volume printing which involves rendering the positive (image) surface of a plate water-repellant, the negative space water-accepting, and wetting the whole thing down. Now, clever as fuck, oil-based ink sticks only to the water- repellant image area. Offset lithography, the method actually used in most modern machines, means that rather than direct contact between image plate and paper, the image is offset onto a rubber roller, which then transfers the image to the paper. It’s called lithography because its inventor, a Bavarian fellow named Alois Senefelder, made his first plates on slabs of the local limestone (litho being Greek for stone).

When pressed as to what a press operator actually does, Reed has little positive to say about the work.

He drones as if it’s painful to recall. “I don’t know, it’s kind of a grind. You’re loading up paper and then unloading it and stacking it, I don’t know how much detail you want—I could go on….” He trails off.

I do want more detail!

The machines can do 4,000 to 15,000 impressions per hour. The press operator must continually adjust the machine to ensure the image is consistent and the paper feeds through correctly, and save proofs of the finished product in case of customer complaints. Job times are determined by book values; i.e., X impressions should be completed in Y hours. No college required, just a good eye for color; and the pay, according to Internet sources, is not the worst—especially for a job facing continual downward technological pressure.

Brian Reed spent most of his adult life guiding offset lithography machines through the process of printing untold thousands of pieces of letterhead, envelopes, no carbon required (NCR) forms, and so on. He was a press operator. It sounded anachronistic to me—I had assumed that the modern printing process was done entirely through an electronic interface. Not so.

When letterpress began seeing a resurgence in the mid-nineties, Reed was intrigued. In the early aughts, he heard about Northwest Portland’s Oblation printers, which had been in business since ’89. So he mailed a letter to the printer and co-founder Ron Rich, via the post office.

At the time, he was unhappily operating a rotary offset machine in Denver. “So I looked him up and said, ‘Hi, I’m a printer, if you ever need help, I’d love to move to Portland.’ So we started this pen pal thing for two years.”

I was reminded of another trade printer who traveled far and wide to learn his trade, always besting his bosses and moving on.

“So did you pull a Ben Franklin, run away from your asshole brother’s print shop, and hop on a shipping container to Portland?”

“He (Ben) could walk in here right now and I could spend one minute showing him the basic function and he could run it. I think that’s really cool,” Reed tells me as we sit at a scrap wood table of his design, in this subterranean time capsule. It is cool, but it doesn’t exactly explain why a 50-year-old printer who, for most of his adult life operated the modern rotary offset printing press, took a step backward into the technological past. Most letterpress artists are MFAs, not trade printers. So I just ask: “Why use old presses when we can use new presses?”

Reed pauses. “I finally found something that suits my temperament. I think it’s a mistake to think that every single person who’s born into our time and place can be filtered through sitting at a keyboard and looking at a screen. Not everyone is suited for it.”

He goes on to say that he worked at Microsoft for a minute in the mid-nineties, and that it didn’t work out for him. In retrospect, putting someone whose work samples were hand-drawn behind a computer to create software clip-art was probably a mistake on the part of Messrs., Gates & Co.

This is unsatisfying. Brian Reed didn’t spend much time working at a computer. When the recorder is switched off, though, we commiserate. Building the electronic infrastructure is what one Is Supposed to Do in our age. To work with one’s hands, unless creating art under the sanction of an MFA program, is somewhat shameful. But what’s inherently wrong with installing electric, fixing cars or collecting the trash? I do aver that this conflict is familiar to all sorts of creative, intelligent, blue-collar types. But Reed has found that rare niche that satisfies all his needs.

None of this is to call Reed a Luddite. His approach to technology is analogous to the sound system in his workshop: an iPhone is stuck into the top of a faux-vintage radio amplified by a cone of chipboard taped to the front. The sound is pure and sweet, despite the digital compression.

His printing plates, manufactured at Oregon Engraving right across the street, are photosensitive polymer rather than the acid-engraved copper of yesteryear’s press imagery. The old method of acid engraving metal plates was known for being expensive and toxic. Sure, he draws by hand. But creating vintage outdoor scenes (inspired by back issues of Outdoor Life and the salmon fishing trips of Reed’s own youth) with the assistance of Artrage software would hew too close to cynical irony for these sentiments.

Chandler and Price platen presses can still be had for a fraction of the cost of a semester at art school. Before electronic printers, lots of people needed presses. “On the bottom of the ocean somewhere, there’s one of these (presses) with the morning’s breakfast menu locked up in the chase,” Brian remarks. He then explains that, on the Titanic, they would have needed a press for the menus. The durability of antique technology is practically metonymic, but the Chandler and Price platen press, proudly engraved Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A., was exceptional even amongst its peers. It was popular in its time because it was reliable, easy to use, and relatively affordable, and plenty have survived years of use followed by decades of neglect.

But then, there’s the process. Unlike a rotary offset press, or pretty much any piece of complex modern technology, the platen press allows the printer easy control over some of the variables of production. Primarily, the platen press will impress any plate or type that’s type high: .9186 inch.

To my mind, the aesthetic appeal of the machine itself is easily as important as the practical qualities it embodies. Unlike this Macintosh laptop on which I type, whose graceful corners and intuitive interface conceal the silent, arcane workings of the circuitry, the platen press is buck naked. And it is muscular. It is also—unlike the screw presses that it supplanted—complex enough to be intriguing. A screw press was Ben Franklin’s press, and his was only slightly more complex than Gutenberg’s press.

I admit that the crevice between the platen (the part where the paper goes) and the chase (the part where the type or plate goes) has a certain, suggestive allure (it is, after all, where the image is born); but the thing is a little menacing. The aesthetic appeal is sublime, in the Burkean sense. Captivating like a venomous snake. Brian says he saw a woman get her fingers crushed “down to the thickness of a sheet of paper,” and I take an extra step back.

But this extreme force, the threatening embrace of the iron jaw, coupled with the touch of the human hand is perhaps what imbues the letterpress card with its almost magical sincerity. In the era of the sterile e-card and the Facebook birthday wish, the revival of letterpress really has breathed new love into a moribund tradition.

Love is the Medium | Mike Allen

[…] fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk')); Tweet !function(d,s,id){var […]