By Jessica Glenn

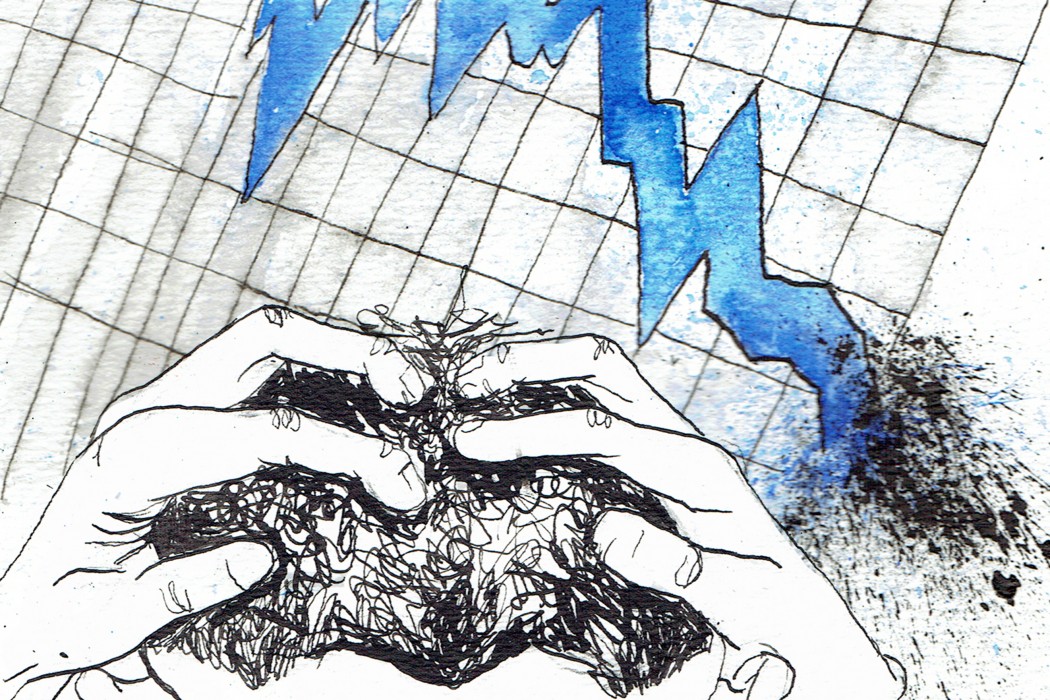

Illustration by Allison Bruns

It was 5:00 Wednesday evening, and in his repetitious way, Roy Datzenrood got in his car, switched on the defrost, and clicked the radio to NPR to hear the Numbers song that went along with the day’s money market analysis. It wasn’t like he didn’t know what the market had done that day. He followed it minute to minute, watching hopelessly for a pattern to make itself clear to him. Stocks remained low, either reasonably stable or falling off for the last four years, and only the hustling speculators were making much of anything.

But today, some news: Nuance was up 52 points. Roy himself didn’t have much Nuance stock, but like any Words Stock advisor, he had enough of the calculated “risky word” to make him a little interest this month.

Roy was a traditional and conservative advisor. This wasn’t necessarily because he thought that traditional and conservative investing was the best way to make money, but he was genuinely unimaginative and feared his litigious clients would get something on him if he took a misstep, and would take their money back.

His standard and unarguably bland advice was something a child could figure out about investing in an hour, if she or he found the right website.

“Diversify,” Roy would tell his clients. “Yes, it’s true that Incendiary has made a small gain lately, with respect to Hollywood breakups, but Mr. Ellison, you are very underrepresented in Pronouns and other Short Words.”

Roy felt Short Words, like bond markets on Wall Street, were the safest bet for the bulk of one’s portfolio. Not that this was a bit novel; everyone felt short words were safe. Their value never skyrocketed, but as long as the population continued to increase, their usage increased around 3 percent per year.

Mr. Ellison had described himself in Roy’s brief investor survey as a “High-Risk Investor.” Roy felt quite sure that Mr. Ellison really had no idea what this meant, as he was only playing with about $20,000 and that was supposed to pay for his daughter’s expensive private college which started the following year. It was time to tell her to go get herself a scholarship, Roy thought, but Mr. Ellison, like most new investors in the Words Market, had become delirious upon hearing stories about people who had put everything into unlikely stocks such as Proactive, Funemployment and Partner 4 (the partner used with respect to marital or domestic status) and become rich beyond their wildest dreams.

Like so many others, Mr. Ellison perused the New Words in English website daily, constantly calling Roy for teleconferences with questions about the value of selling off some Ebonics and Café Americano, for a little Breadcrumbing, Flexitarian, and Unfollow.

“Yes,” Roy would say tentatively, “it’s certainly good to do your homework, but have you thought of Blog? The price is high, but shows no sign of falling off, and you have the benefit of investing in a reasonably new word.”

Mr. Ellison would hum and haw and invariably leave his portfolio as it stood: flat lined.

Listening to the Numbers song on the radio comforted Roy during his long commute home. He blanked out the news of his father’s illness, the approaching holiday season, the disastrous political climate, and the general lack of value in his life by concentrating on the predictability of a song. Or, three songs, actually. NPR played a happy song if the market was up, a sad song if the market was down, and a soft swing if the market was flat.

The little songs had wormed their way into Roy’s subconscious, turning the business of capitalism into a fervent metaphor. He only wished the song could continue a bit longer, or perhaps be a bit more complex, to somehow let him know that although the market had net gains for the day (Happy!), the Mutual Funds Phrase Market had ended lower (Sad!). It needed more nuance, he thought . . . then smiled to himself, unduly pleased.

Roy had actually heard a bit of the buzz about Nuance the week before from his client, Mrs. Irvington. Mrs. Irvington was an ancient woman who sort of reminded Roy of a coy Greek monster. He couldn’t remember the one, exactly. Three heads? Turns one to stone? Crushes ships at sea?

She was always talking about her Cheney connections, and she did indeed have a decent portfolio, conservative enough for Roy but with enough plain old capital to make it hard to lose too much. Roy always wondered, though, why Mrs. Irvington had chosen him as an advisor if she were really so well placed as all that. He assumed she had either confused him with his father or assumed that brilliant investing was somehow genetic.

For some reason, Mrs. Irvington (not on a tip from Roy) had bought a goodly amount of Jones 3 (a strong craving) in 2004, and it had made her a pretty penny in the last few years. This seemed to keep her reasonably happy, and she made appointments to see him in order to gloat about her superior knowledge of investing.

In their last meeting, Roy heard from Mrs. Irvington, who heard from her cousin, Ms. Lucille Laprince (who was a close friend of Ann Romney) that Mitt Romney was beyond thrilled that Obama had used the word Nuance in a recent campaign speech response to the Tea Party’s highjack of healthcare. And right before Christmas, too. He could actually see Mrs. Irvington capitalizing words in her head for effect.

“Ann says Mitt was much too clever to use a word like that, not in a campaign speech. Nuance, by it’s very meaning, is not a sound byte, you see, dear. But the Romney family is delighted. If they manage to make an issue of it by baiting the Tea Party supporters, they will significantly increase the word’s usage,” Mrs. Irvington murmured in a slyly confidential way, looking at her thick aged nail, manicured perfectly, then at Roy from the corner of her eye.

“And we all know who owns the majority of Nuance…?”

Roy had no idea and wasn’t great at thinking on the fly, but he smiled at her encouragingly.

“The Romneys, of course! My God, man. My five-year-old great-granddaughter knows that.” Mrs. Irvington paused for a second, absolutely delighted with the breadth of her knowledge.

“A good time to buy a little Nuance I would think, hmm? Although”—she blinked girlishly—“don’t pass this around, dear; they’ve really been cracking down on the insider information bit, which I find simply ridiculous. One can’t help having connections, and one can’t help having connections help one, am I right?”

She was absolutely right, thought Roy, and he pulled into his driveway.

Roy’s wife, Tia, was a caterer and perceived herself to be a talented investor as well. In fact, talented hardly covered it; undiscovered genius was perhaps a better description.

Tia had simply amazing 20-20 hindsight when it came to Words Investments, which was not nothing, seeing as Roy resisted even historically prosperous but risky endeavors.

Roy got out of his car, stiff after a 55-minute commute, and walked through the December curb slush to the little house. His hard-faced tabby strutted up to him confrontationally then tripped Roy in her effort to reach the front door as the same time as him.

Tia was in the kitchen moodily smoking a cigarette and stirring a reduction of jus from a gingered pork roast.

“Why didn’t you buy Blackened in the eighties? Was I just born a genius? That’s what I want to know. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again—I could have been living the lush life.”

“Hi, sweetie.” Roy kissed his wife. “How was your day?”

“I worked on a Chanukah party menu for the Goldman family—who, on top of being kosher, are all also allergic to both eggs and wheat. The teen daughter is newly vegetarian, which is upsetting her grandmother, and the father doesn’t eat salt. It was less than phenomenal, obviously.”

Roy took off his jacket and shoes and sat on the couch to read the Val-U Coupon booklet, which had arrived in the mail that day.

“Oh, Roy, your dad’s personal assistant called. He’s getting some more tests done or something, I didn’t really understand exactly what the guy was saying.”

“My dad? Is he worse?”

“I dunno, maybe you should go see him, or talk to his assistant or something.”

Lymphatic, thought Roy. I should invest in Lymphatic. Then he shivered at the thought of his own daring to invest in an un-suggested word.

“What do you think about Lymphatic, honey?”

“Is that what he’s got?”

“I’m not talking about my dad. I mean, it could be a little risky, but—”

“Oh, Lymphatic. I don’t really think so. Everybody’s saying that the big winner is political sound bytes. You know, Economy, Freedom, Jobs… Things like that.”

Roy knew this, of course.

“But sweetie, I’m thinking long-term: the Baby Boomers are getting older, it would be a sort of long-term investment, you know?”

“What about just going day-trader style with Christmas, Holly, and Eggnog, or whatever?”

“Statistically, holiday word trading is not a good investment, honey. Everyone buys at the same time, everyone sells at the same time.”

“I just can’t believe you didn’t get Flip-Flop when I told you to. We would have made bank last election. I mean, am I a genius or what?”

“Oh, come on. You told me to buy Flip-Flop 2, the sandals, and that was because of some sale you went to at Nordstrom’s Rack. Not the same thing.”

Tia sniffed haughtily. “You must have misunderstood me.”

Roy’s father, Ellery, was as illustrious a Words Investments advisor as it was possible to be. He saw the movement and flow of words like a grand and limitless opera, following the rhythm and cadence of a conductor known only to him. Ellery effortlessly predicted the rise and fall of a hundred thousand words, simply by the way he saw that they would be written into the music of speech.

Ellery saw words in the universe like a four-dimensional flipbook of pictures. When we flip the pages, the little man is seated, and then he jumps. We start again at the beginning: the man is seated, and then he jumps again. The cartoon is over. But Ellery saw the man, the man seated and the man jumping, all in motion, all at the same time, and the cartoon never finished, just infinitely kept drawing itself new pages. This was his lovely and eternal Word Concerto.

You can surely imagine how difficult this was for Roy.

It wasn’t like his worry about his father’s illness wasn’t consuming him. It was, but not the way that fire consumes tinder, or water consumes rock. Ellery’s ill health ate at Roy like an enormous, internal, parasitic secret. It swallowed all of Roy’s dinner before he had the chance to eat it. It swallowed his well-being before he had the chance to tuck it comfortingly around himself. It was sucking the life from him quickly, but from within, while the outside shell of Roy Datzenrood could hardly even understand the injuries that his damaged soul was sustaining.

The next day was Thursday. Roy had six clients scheduled: three very mundane, one financially mundane but physically attractive, and two rather pushy clients who made a habit of questioning Roy’s credentials while remaining on his roister. Irritating.

The morning passed uneventfully. The financially mundane but physically attractive Ms. Gibbons wanted to know if it would be prudent to get married before or after the end of the fiscal year in order to have the greatest possible tax advantage. This was a bit of a downer for Roy, who liked to imagine her single. But she wore a sexy translucent gray blouse, and he could see her lacy black bra under it. That pretty much made up for it.

Roy’s 1:30, Mr. Gordon Kean, was as Roy expected him to be: pushy and confrontational. Roy’s 2:45, Mrs. Lorna Dunn, the same. It bothered him a bit more with Mrs. Dunn, perhaps because cowing to a man was a bit less humiliating to Roy. He chalked it up to experience. There were few women in his life. His own mother had left for who knows where and dropped him in front of the building where his father worked, on her way out of town. Until that point, Ellery did not know he had a son.

Roy left the office at 4:55 and drove to Holy Trinity, the hospital where his father was staying. He wished he had brought something, but flowers would never have done for Ellery and chocolates were laughable. Still, his hands felt dangerously full of helium, and any offering would have been enough to relieve the desperate desire to weigh them down.

Ellery was a large man. Not adipose or fleshy, but simply imposing. He wore his body well, and now at 70, Ellery was no less dignified than at 40.

Nevertheless, hospitals don’t tend to make allowances for the foolish desire for dignity, and Roy expected to see his father at least somewhat transformed by the pastel and antiseptic atmosphere.

He tread each step in to the hospital with faulty intention and guilty trepidation, wondering if a change in his father’s appearance would make him feel peevishly better about himself or cause him to fall apart in pieces.

It was room 317, which probably meant third floor, somewhere. Ellery’s assistant had emailed the room number and visiting hours to Roy earlier in the day, and Roy let the sets of numbers cycle through his head uncollected, pushing and shoving all unwanted words to the periphery.

The room was much too easy to find. Roy had counted on getting lost for a few minutes, employing the help of a friendly candy striper, and entering his father’s room with the nonchalant air of a happy-go-lucky loafer. But no such luck.

He slowly opened the door without knocking, because, of course, knocking would have been useless, and he walked inside the room.

Roy had thought his father might have been napping; he had thought his father might have looked frail; he had thought Ellery might have looked weak, or ill, infirm, pained, or afflicted. But no. Ellery looked as he always did: resplendent as a king. He wore the baby blue hospital gown like a regal toga—and with the utmost grace, he pulled out a golden marker and the collapsible, transparent glass sheet on which he always wrote.

Roy’s father couldn’t speak or hear. Instead of making Ellery look feeble, it seemed instead as if the people around him were impaired. Their petty struggles to understand Ellery’s clear rationality and the depth of his insightful thought were pitiful to watch, in the same way that it is slightly painful to observe an old man helplessly drip food out of his mouth, or a woman inadvertently trail toilet paper from a sensible shoe.

Roy walked over to the bed, as always, unsure of how to proceed. He patted his father’s leg under the cover then immediately regretted it, making an association between the gesture and his homely tabby cat.

Ellery looked at Roy calmly. This was something Roy was familiar with but still not at all comfortable. The irises of Ellery’s eyes were yellow and had an uncanny clarity and chill to them that reminded people more of blue. Roy thought Ellery sucked up his soul when he silently examined him in this way, and he squirmed under the intensity of the stare.

Calmly, Ellery picked up his glass sheet, unfolded it, and spelled out each word in his inimitable script:

Dying, sath the man who writes, is our duty and our right.

Roy took a great gulp of air and felt himself spontaneously blushing.

“Ellery, what do you mean? You look fine!” He knew he sounded like an idiot, but this, too, was familiar.

I am dying, Ellery wrote.

A chink, a crack in Ellery’s façade appeared. It was so infinitesimally tiny, no one would have noticed it except Roy, who suddenly felt the strong urge to throw up.

Don’t vomit, Ellery wrote.

“I won’t!” Roy exploded.

Ellery closed his eyes for a moment and Roy took the opportunity to swallow hard a couple of times. When Ellery opened his eyes again, he looked slightly tired. He picked up his writing sheet.

The words sing. Song wrong, gone the melody of long antiquity to return again.

Roy was frightened—his father seemed to be babbling.

“I don’t understand, Dad.”

The music will end, Should end, and conclusion of the last movement began, ended… Ellery erased what he had written and started again at the top.

Four months ago. And Coda began.

“I don’t understand, Dad!”

Ellery looked frustrated by Roy’s apparent stupidity and continued writing.

It was to be a reaffirmation of the opening melody, an acquiescent but slightly dissident rendering of the original peal of bells, of shells, clapping on the land of sand, tongue of man.

Ellery paused and looked at Roy intently then erased and started again at the top.

And the manmade screen bites eat at the nearly consummated whole, folding and breaking at the mold.

Roy thought for a second.

“Politics? You mean sound bytes are ruining the music of language?”

Ellery finally looked at ease with himself again. He smiled gently at his son and let go a prolonged and premeditated breath in affirmation of Roy’s immature but growing comprehension. As he exhaled, all of the life seemed to drain out of him.

Roy watched Ellery mysteriously whither away. The breath that Ellery released seemed to contain all the vigor he had privately stored for 70 years—and there the air went, like nothing at all, hissing and stumbling, ruining the fierce sterility of the hospital with its feverish and circuitous dreams.

Had Ellery lost his gift to see the patterns of words? Was he simply seeing his own death? Though rheumy now, Ellery’s yellow eyes saw through Roy’s question and he picked up the marker again.

You must do something. The market has ruined the music.

Ellery dropped the marker and reached his hand up to Roy’s arm. Roy could see it shaking ever so slightly. Ellery squeezed Roy’s forearm for seven seconds like a rest before a final crescendo, lay his arm back on the bed, closed his eyes, and died.

Roy looked at the body of the old man. He lay down next to Ellery’s corpse and sniffed the familiar pine-bark smell of his neck. He stroked Ellery’s hand softly at first with a finger, then dug the edge of his nail hard into Ellery’s palm, cutting into the skin slightly. But Ellery was gone.

Roy thought perhaps if he exhaled deeply enough, he could breath the life out of his own body as well. He inhaled deeply to ensure a dramatic final exhalation…but as he inhaled, he heard the sound of music. Roy inhaled deeper still, and the music became more pronounced. It wasn’t notes, or beats; it the most glorious sound Roy had ever heard—the cosmic circumvolution of all utterances in the cosmos: their birth, their death, and their resurrection, all according to a sublime and radiant composition. Roy took a third breath and instantly understood what his father had said: the Coda was incongruous in relation to the whole of the piece. The words had lost their place.

The Conductor was dead.

Roy felt a presence behind him and turned. A furious-looking nurse stood behind him, red-faced from screaming. Roy watched her carefully, but none of her noise interrupted the shifting shapes of sound in his mind. Roy gathered his coat, his father’s glass, writing sheet, and golden marker, and walked out of the room.

It was 6:00, and Roy got into his car and drove home.

“I wouldn’t think you would have the gentillesse to wish me a good evening for a change, now, would you?” said the tabby distinctly, walking sulkily up to Roy’s car door. Roy looked into the cat’s eyes and closed his own slowly, blinking his acknowledgement.

“Well, howda you do? The man finally learned to speak. A Christmas miracle,” the cat said, smiling and purring to herself.

Roy opened the door and walked into the kitchen. Tia was massaging the loin of a lamb with a dry rub of fleur de sel, minced rosemary, and coarsely ground green pepper corns. She threw herself into it, working fiercely from her shoulder with a practiced and intimidating hand.

Roy watched her from the doorway and felt his belly beam with love for her.

“You’re home late, didja see your dad?” She paused a second, looking up at Roy. “Why do you have his glass thingy?”

Roy smiled at her.

“What?” she asked “What?”

Roy pulled the marker out of his pocket.

Hi, Sweetie, he wrote, how was your day?

“You are such a freak. Your dad needs that, you know. Why didja take it?”

His belly stopped beaming. The music in his head made it difficult to remember how to react to his wife. He thought for a moment, then scrawled on the glass: Conductor is dead.

It was 8:00 Friday morning. Roy got into his car to go to work. He had five clients scheduled, five little bundles of atoms seeking answers they had no expectation of receiving. Five little energy packages questing after a magical pattern that might reward them in points, which translated to excitement, which translated to money, which translated to comfort, which translated to security, which translated to happiness—which none of them actually believed was possible.

There was no escaping the mandate his father had made. You must do something, he had said. But Ellery hadn’t done anything, from what Roy could see; he had just died in response to a cosmic mishap. Roy was not quite sure how to proceed. It was true that he had somehow been bequeathed his father’s ear for the language of the divine, but Roy was still Roy. And this was a crappy place to begin a day in the office.

The office was a gray building, five stories high with shoddy trim around the windows and thin, industrial gray-blue carpet throughout. Roy’s office was on the fourth floor, and he generally took the elevator. Today, he walked up the dark and unfamiliar staircase.

Can we even imagine the music Roy heard that morning? The points of dust that danced in the pockets of fluorescent light at the landings sang to him of secret anguishes, of lost and unbearably carnal loves from an age before time. The creaking of his own steps incorporated itself into a song that predicted passive doom, the foreshadowing of an eternal silence.

Opening the door to his small suite Roy saw his secretary, Tilda, in front of her desk. Her purse was open and filled with about 27 office pens. She resembled a three dimensional slide, and she didn’t move as he walked in.

Roy unfolded his glass sheet.

Good morning, he wrote.

Tilda finally moved to take a breath.

“You know? You know, what’s happening?” Tilda asked.

Roy listened carefully to the instrumentation of his mind. Yes, it continued. The monstrosity of the failed coda had reached a painful crescendo.

“I’m leaving.” She spoke defensively. “Everybody’s leaving. The Words Market is in shambles, everything’s been sold.”

Tilda appeared confused by her terror and clutched nervously at the office pens.

“People are now reporting serious trouble speaking at all. I must leave. I must collect my… chil… ki… drens…”

She put her hand on her mouth, suddenly hysterical, pulling at her lip like a monkey. Tilda slapped her own face lightly in an effort to collect herself, zipped her purse full of stolen pens, grabbed her coat off the office coat tree, and ran out the door.

Tia had left the night before. She finished baking the crusted lamb, wrapped it in tinfoil, and drove away with some clothes, shoes, birth control pills, and the newer line of Avon beauty products. Her departure had nothing to do with the Words Market; she just wasn’t down with deaf-mutes. It didn’t surprise Roy in the least.

The office was now empty, but it was hard not to become distracted again by the tragic ballads of the floating dust particles. It was, Roy realized, the beginning of a universal death. He could detect it, a sort of fibrous tar smell mixed with the rotted odor of composting roses. But there was really no time for nostalgia. Roy walked out his office door in the direction of the Words Stock Exchange. It took him 32 minutes to reach Word Street.

An Orange Alert was in effect, and armed guards were meant to be posted at every entrance. Roy saw the last guard wander off, mumbling something about a dog, and Santa Claus. Smartly dressed traders were still straggling out, looking confused.

“Walk, drive, bar, snow,” one man muttered idiotically, perhaps to another man walking fast next to him.

When Roy finally entered the floor of the exchange, the last trader scuttled out. As he left, the echo of his last word bounced, “SELL … ELL … eelll,” off the marble for a few seconds then dissipated into the air. Roy examined the empty platforms, the papers scattered over the floor, the laptops dozing lazily, and then, right in the center of the room, he saw the Words Computer.

The Words Computer was purported to be the product of a team of 34,000 computer geniuses from around the world who had worked for 15 years to perfect an impeccable way to track the quantity of each uttered word. It was correct to the nanosecond. Roy walked behind the imposing gilded desk on which the vast computer stood, and examined the huge monitor. It was impossible to read the entries because they flashed across the screen so quickly. These entries were shunted to other computers which tracked linked groups of words, and in this way identified the direction and flow of the market.

What was at first simply an animated gray blur on the screen began to slow into identifiable words.

Economy

Roy read, though it was difficult, through the fog of entries.

Mama

Goal

Holiday

Freedom

Sale

Mommy

I

Reelection

It was becoming easier; the words seemed to be slowing.

Socialist

Chief

The words were slowing. It was unthinkable, but the words on the screen were now only coming in a few at a time.

A

Momma

It

Honor

No

Now the impossible: the screen was blank. Roy had never heard such silence in his life.

But wait! Here! One more word. Someone somewhere was able to speak one more word.

Freedom

It read.

Freedom

Freedom

Then nothing again.

Roy opened his mouth and screamed, but all he heard was a mother rat in the corner under some damp newspaper, softly singing a carol to her skittish babies. He unfolded his glass sheet and wrote upon it in huge gold letters:

Illumination!

Illustrious!

Drizzle!

Sizzle! Morbid! Kaleidoscopic! Voracious! Baptismal! Malevolent! Magnificent!!

Roy erased and wrote again with inhuman speed. He simultaneously looked at the monitor, mouthing the words he wrote on the glass sheet, checking to see if any of them had been recorded. The screen had remained black for more than 28 seconds.

He watched the monitor, carefully counting to 60 twice, willing the screen to show a word. Any word.

As if in answer, a word slowly floated to the surface of the screen like an air-filled cadaver rippling up the surface of a still lake.

Freedom

It said again. And said no more. Roy took a breath in and slowly exhaled. The music stopped.

How interesting, Roy thought to himself. His father had been quite right: the finale did not fit at all. He listened as the silence truncated the mother rat’s song mid-note: Silent nigh… severing the dying tone before the tail end.