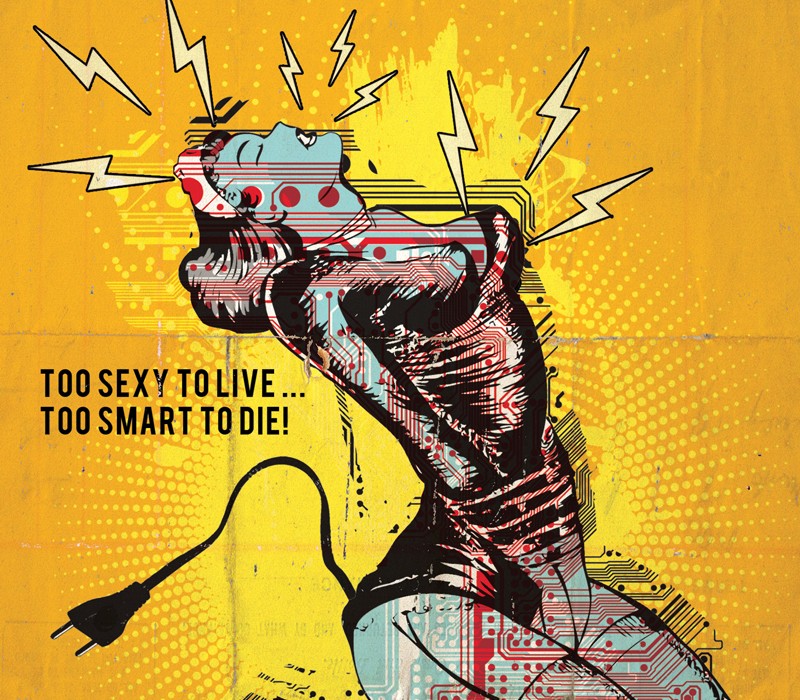

| From PDX Magazine writer Mykle Hansen, a new novel, I, Slutbot (Eraserhead Press, April 2014), explores a future world where the supreme leader is a super-powered titanium and latex sex machine who protects her mechanical subjects from the dangers of fleshy beings, including a horde of lovesick zombies and a Martian beefcake who can’t hear—or even spell—the word “no.” We are pleased to present “The Uses of Poetry,” a chapter from the novel, narrated by Slutbot’s typewriter Smith Corona. |

By Mykle Hansen

There are zombies, and then there are zombies.

I used to watch them, in those years before Slutbot rescued me from the blasted-out junk store window where the world left me as it fell apart. I sat in that window, half-buried in shattered glass and radioactive debris, and watched the zombies shamble by.

I watched police zombies patrol for nothing, or beat corpses slowly with their batons, or squawk static replies to the static from their radios.

I watched zombie joggers, their forearms raised, searching for the lost spring in their step as they slowly orbited their old tracks.

I watched zombie gamblers lurch in and out of the casino, pry on the locked arms of famished slot machines, crawl across the ground as if searching for lost coins.

I once saw a zombie dog catcher lay a trap for the desiccated corpse of a poodle. It was perhaps the most intentional thing I ever saw a zombie do. Slow as an afternoon shadow he dragged a shredded net across the ground in front of the stiff furry thing, then sat and waited for the animal to take the bait. To my knowledge, he is waiting still.

I believe that in every zombie one can see, if one watches long enough, the reflexive residue of a former identity swirling in a slow loop of pure habit. Zombies are human habit personified, free of meaning or intent. Repetition in flesh, patterns of behavior in aimless motion like the dust in sunbeams.

Some habits are worse than others. The zombie who has invaded my mistress’ garden, Hhjk, exhibits a particularly tragic and awful habit.

He writes poetry.

Behold, his latest masterpiece:

iukji zzxzz

ikiii zxczz

mmmmmmmmmmmm,,,

¢

Bravo.

It’s hard to critique such abstract work, except perhaps to mention that his ice-cold clammy fingers on my keyboard fill me with a wretched loathing for the sad creature and his line-noise doggerel. As achingly heartfelt as I know it to be, it is crap. In all my steel and bakelite years, if there is one kind of writing I can speak of from experience, this is the kind: crap. Crap of the most inarticulate, underwraught and tedious flavor.

Hhjk’s only animating habits appear to be falling hopelessly, stupidly in love and desecrating paper with gibberish. Out of all the zombies in the desert who have tried to pick and claw their way into Slutbot’s garden, which one succeeded? A zombie soldier? A zombie fireman? A zombie cat-burglar?

No. A zombie poet,

with zombe feelings.

Slutbot is curiously unconcerned by him. Since the night he inserted himself in our private business, the other zombies outside the castle have fallen still and silent — perhaps Hhjk is their proxy, somehow? Perhaps he is the price we pay for safety? — and so she has begun to spend evenings here in the garden again, humming a piece of music while she affixes nanorobotic monitors to the trees and laces laser-optic networks between the rocks. As she works on this mysterious business, Hhjk the zombie lurches slowly to and fro after her, with those dead and wilting roses clutched in his outstretched hand. If ever he catches up with her — the snails sometimes outrun him, but even a snail gets where it’s going eventually — then he crumples down to one knee, a kind of half-bow, half-collapse, and attempts to gnaw on her toes.

The first time I saw him try it, I expected her to blast him full of new assholes. But she only stared, for just a moment, then flew away. So I considered that she might be testing him, experimenting on him. Trying, I assumed, to find a new solution to the age-old zombie problem. Why else would she leave him so un-incinerated, so dangerously mobile?

But the second time he pulled this one-knee toe sucking stunt, I watched as she stood there and allowed it, dropped her laser shovel and set aside her megaspade, closed her eyes and endured the chill of electricity leaching away watt by watt. She didn’t seem alarmed, paralyzed or trapped, merely curious. They did that, the two of them right in front of me, for a minute that felt like a year, before Slutbot finally struck him across the skull with the megaspade and he went temporarily still, briefly a proper corpse. Then she wandered off and disappeared down her staircase, uninjured as far as I could tell, and with an expression on her face I had never seen before.

Eventually Hhjk the poet popped back out of proper death and slumped back to the writing table, where he somehow managed in less than an hour of clumsy scraping and thumping to insert a fresh sheet of paper, diagonally, in my platen, and then to compose this joyful ditty:

!!!!””””#### $$$%%%%%

idh4n mmmmmmmmskia jfu4jx04jfus jdk58gje uvn

…..!

It’s a love poem, if you hadn’t guessed.

A poet in love is a menace. I should know; I was once in the employ of such a wretched creature.

That poet lived an exhausting, restless existence in a small converted garage in a scenic oceanside town. His three great possessions were myself, his bicycle and his overstuffed shelf of novels, poetry and pamphlets. He also owned a particularly stupid black hat, which he believed conveyed some dignity upon his prematurely bald head. He was a hideous young man. Thick black hairs sprouted from his nostrils, knuckles, ears, neck and every other inappropriate place. Instead of shaving, he bought a hat.

He owned me for only a few years before he perished in an earthquake — the poetry section of an unreinforced masonry bookstore fell on him — but in that short time he managed to fall in a great deal of love. That was his worst habit, and of course I was spared no detail. He’d come speeding into the garage, throw his poor bicycle to the floor, hurl himself at my keys and bang out long, disjointed lists of his latest obsession’s body parts: oh her hair, oh her lips, oh her sandals, oh her elbows, and so on. Furthermore, each body part was like a thing; that’s what made it poetry. Oh her breasts like hills, her breath like zephyrs, her fingernails like amethyst, her voice like the song of waterfowl, et cetera. He’d go on like that for pages, rewriting, sharpening his metaphors, grinding them against his ardor, until he felt he’d condensed his obsession into a page or so of brilliant paean. Then he’d rush off to deliver that amorous parts catalog to whichever young woman or man it was meant to resemble, and await a reaction.

Few reacted well to this. But the ones that did became his companions, for a little while each. Humans did love to be loved. However, whenever this poet did manage to coax some glowing beauty into his pube-flecked orbit, invariably he soon became compelled to enumerate his or her flaws, both in poetry and in person, and to slowly pick at and tear into the love he felt, using the bluntest, cruelest words he could find — and here he had some talent — until he succeeded in driving the unfortunate victim away, into hiding or worse.

Next came drinking. Red wine, followed by absinthe, chased by whiskey. With alcohol he punished himself, alone in his little garage with no friends to console him or stop him. He punished me too; he beat me, threw books at me, smashed glasses of whiskey on me. And when he was almost too drunk to stand he’d struggle onto his bicycle and ride off into the cold and foggy seaside night, screaming obscenities at the moon. He returned from such expeditions with bruises, scraped skin, broken teeth and a bent-up bicycle. He’d be sick and listless, surly, muttering hatred under every breath, vomiting freely in the yard, sleeping all day, wandering the sunny streets of the town under a cloud of self-made despair … until, soon enough, he spotted some new wonderful target for his obsession, crossing the street or minding his or her own business at the grocery store, and the tragic cycle commenced another loop.

It embarrasses me to recall how deeply I once believed in him. I thrilled, actually, at some of these awful poems. He did terrible things to me, and used me to destroy innocent others. Together we wove silken traps to ensnare human hearts, sting them and suck them dry.

But at least he used me.

My mistress has begun a new project now, a new cryptic set of daily activities. Instead of nurturing these plants and insects in her garden she is now measuring them, networking them, placing surveillance probes in each living being and collecting all that sensation into snaking bundles of glass cable that crisscross the ground. The cables trip up the zombie’s feet marvelously well as he stumbles ever toward her. She works at super-speed, a dervish of activity, connecting everything she has done here in this green place with that other project that remains a mystery, that deeper system underground. I once thought the garden contained all her secrets, but now I see it is just one layer of her defense, one more moat of her castle. The point of it all, whatever that may be, is hidden somewhere in the catacombs, down where the Wumpus once roamed.

Soon she’ll take me there. She wouldn’t have brought me here if she didn’t intend to take me into the heart of her fortress, to the center of her perfect self. Soon, I’m sure, once the current set of activities are settled and she has time again to relax, we will ditch this zombie and continue our inward journey, our mission, our opus.

But I cannot help noticing that she finds time for him … for Hhjk the zombie, the love-smitten toe sucker. He follows her, he waits for her, she’s far too busy for him, and yet —

Tonight, as the sun set in the mirrors overhead, she came to him.

She stood before him, hands on her hips, her regal brow upturned, and gazed down her nose at him —

He knelt, or fell over, again at her feet, and laid his sick hollow leather skull against her perfect titanium toes, and nibbled his empty jaw against them as if to kiss —

And I saw her tremble. And I saw her smile.

LitHop: a Literary Pub Crawl | PDX MagazinePDX Magazine

[…] Hansen is most likely reading from his most recent novel I, Slutbot, which PDX Magazine has an exclusive preview of here. The book’s robot-themed release party is this weekend at […]