I am a former Soviet, smuggled over the Iron Curtain in my parent’s gonads like some Cold War technology and assembled in the USA. The other night, I was at the Alberta Street pub, listening to the musings of local Slavic rock band Chervona. I should have been drinking vodka. Instead, I was slowly nursing a New Belgium 1554 Black Lager for a period much shorter than my own gestation but surely a longer process than usual.

It was like reading a fine book. Each sip was a page revealing another character. In a moment of emotional flavor, at only 5.6 ABV, I could feel the warmth of the beer moving slowly through me. Its nutty taste made me happy, and its chocolaty aftertaste gave me the feeling of being privileged, decadent, and pampered. Soon my bar stool buddy and I were having an intense discussion about the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. You would think that when two former Soviets discuss history, things might turn crazy quickly. But, since we were drinking craft beer and not vodka, the conversation stayed nice and calm.

It dawned on me that the craft beer I was drinking is revolutionary in itself and that drinking it is a radical act. A subtle piss in the face of authority, an act of defiance against the state regulators, brewing conglomerates, and the distribution monopolies of corporate beer. Unlike our fathers, who drank soulless beer, never questioning it, we have taken control of where our beer comes from and what goes in it. Beer is not just a beverage; it is a catalyst for community, prosperity, and conversation.

The beer made me feel quite bohemian. Soon, we were discussing a personal hero of mine, the father of leftist journalism, Jack Reed. The American reporter still lies in Russia, entombed in the Kremlin wall next to Lenin.

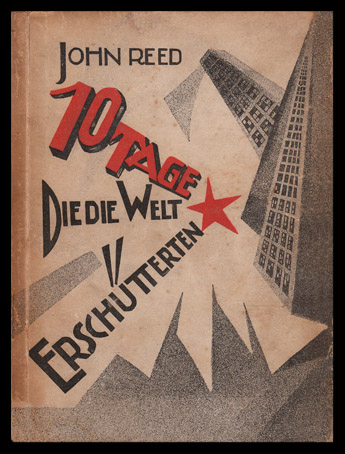

My bar companion told me that Reed was born in 1887—in Portland! This amazing new fact set me in to action. And being a hound for history, before I finished my beer I had learned that Jack spent his formative years playing in the hills of Goose Hollow. His father was a successful businessman who was made U.S. Marshal by Theodore Roosevelt. He exposed the scandalous behavior of his peers in the Portland elite. Young Jack watched his father ostracized because of that. This played heavily into his psyche, as he went on to become one of the greatest chroniclers of the struggle of the labor movement in the early 20th century. Reed’s book, Ten Days That Shook the Earth, was immortalized by Warren Beatty in the film Reds.

I had my mission: I was going to find Jack Reed’s ghost—or at least his spirit. I headed out into the night. But first I stopped at nearby Beer Mongers Bottle Shop and looked for a proper beer to summon the ghost of Reed. I searched a while, waiting for a beer to call out to me. Boneyard Brewing? Possibly. Or maybe Dead Guy Ale? No, it wasn’t in the name. It had to be a beer Jack would have liked.

I guess I looked lost. They have so many different beers.

An ale angel, Kris McDowell, from Brewvana Tours, appeared next to me. “You looking for something special?” she asked. I told her I needed a beer suitable for conjuring the ghost of a member of the International Workers of the World (IWW).

She handed me a can of The Kimmie, the Yink and the Holy Gose Ale, saying, “This one, of course.” I noticed the purple can looked like soda pop, good for street drinking. She informed me that it was classic dry ale. No hops to get between me and the spirits. And it’s under two bucks a can! That was it. I had my beer.

I bought a few cans and headed to my first stop: 521 NW Davis, where, 100 years earlier, the IWW Hall had stood. In 1914, Jack called that building “the liveliest intellectual center in town.”

Now it was just a brick wall. As I took some pictures of the blank wall, a group of young street activists from Night Strike asked what I was photographing. It was a warm spring evening, and they were handing out food, and witnessing, and talking to the street folks.

I proceeded to reel them the story of my beer-induced mission to honor Jack Reed. I had just learned that, in the summer of 1914, Jack had just returned to Portland. By then, he was a national celebrity—he had ridden with Mexican Civil War general Pancho Villa, and had written the book Insurgent Mexico about it. He had covered union strikes all over the country and won praise for his coverage of the Ludlow Colorado Massacre, in which John D. Rockefeller sent Pinkertons to kill three hundred striking coal miners and burn their families in their homes.

In that summer of ‘14, Portland was a lively place. Revolution was in the air, and radical ideas were shared and pushed to the national forefront (Portland would become a hotbed of the radical leftist movement of the early 20th century—which lasted until the city police formed the Red Squad and put the leftists down.). One night that summer on Davis Street, Jack met anarchist/author/activist Emma Goldman, who was living in Portland at the time. It was also the summer Jack and Louise Bryant met and fell in love, set to embark on their amazing love story.

To the kids of Night Strike, I was just some crazy history buff on a beer-induced rant. While I talked about the long fight of the human rights movement, activists with clip boards walked around us with petitions for ending the prohibition of pot. I was taken by the irony, as it was also the 100th anniversary of the Oregon prohibition, voted in a full six years before the national prohibition. It was meant to curb the open drunkenness and general rowdiness of Oregonians. But it only served to place the chains of oppression on the brewers and drinkers of fine and noble beer. (State prohibition was overwhelmingly voted out in 1933.)

I stepped off my soapbox, crossed the street, and stood on the spot where Jack and Emma would have met. I opened the Holy Gose Ale and stood there, reflecting. That first taste was like the salty sweat of workers. An extremely bitter, dry taste, without a hint of hops, was quickly followed by a refreshing buzz that warmed me. I poured an offering of beer on the ground where Jack and Emma might have stood.

Feeling imbibed by the spirit, I took my remaining beers and headed up Burnside to Washington Park, on foot. Past the hookers and sailors, boiler-makers, and bankers. I had heard that the staircase and a piece of the old wall of the house where Jack was born still remained, and I intended to bring the rest of my beer there and wait for Jack’s ghost.

It was very dark now, but there were still a lot of people wandering in the thickly wooded paths. I stumbled around for a while, not finding the steps, when I came upon a couple of gentlemen of no fixed address, reclining on the earth. I told them I was a beer critic for a local magazine and I wanted to know what they were drinking. They laughed at me and said, “Oly.” I asked them if they knew where the stairs to the old house where. They pointed up the hill. I handed them one of my beers and asked them what they thought. One guy cracked open the Holy Gose and took a sip.

“Hmmm.” He rolled it around on his pallet. “Interesting ale. It gives way to earthy undertones and hints of citrus, followed by a salt-like dryness and a tangy effervescent finish.”

Wow. “Thanks,” I said.

The other guy took a sip. “Damn, this beer is bitter. I’ll stick with my Oly. Thanks.”

I followed their directions up the hill until I came upon this staircase that seemed to go up to nowhere. This must’ve been it. I saw a big hunk of old stone wall at the top. I climbed the crumbling stairs and sat down in the dark, at the top, and set to beer drinking. The warm buzz of the Holy Gose put me more in the mood for a haunting. I thought about Jack’s writing, and how as a young man he inspired me to travel, observe the world, have compassion for humans, and work for social justice. I imagined the young Jack running around me, through the woods, as a boy. I read aloud a poem a homesick 15-year-old Jack had written in 1905. Remembrance can be radical, too.

The wind has stirred the mighty pines

That cling along Mt. Shasta’s side,

Has hurled the broad Pacific surf

Against the rocks of Tillamook;

And o’er the snow-fields of Mt. Hood

Has caught the bitter cold and roared.

— “Twilight” by Jack Reed, 1905

A hundred years later, I can still feel Jack Reed among us. He would’ve liked the Portland of today, I think, filled as it is with freethinking, beer-making, optimistic young rebels. I poured a bit of beer on the steps. I heard rustling through the trees, a faint whisper that made me crush my can just a bit. “Bring me home,” the voice said. “ I want to come home.” I think it was Jack telling me he wants to be returned to Portland to be buried. But that just may have been the beer talking.

— Lenny Hoffman