“Counterpoint” by Jon Gottshall

Gallery 114, 1100 NW Glisan

August 4-27, 2016

Opens Thursday, August 4th, with pre-opening artist’s talk Wednesday, August 3rd, from 7-9 pm

The exhibit also features Megan Paetzhold’s multi-medua installation “Studies in: Amblyopia” in the south gallery

Story by Jon Gottshall

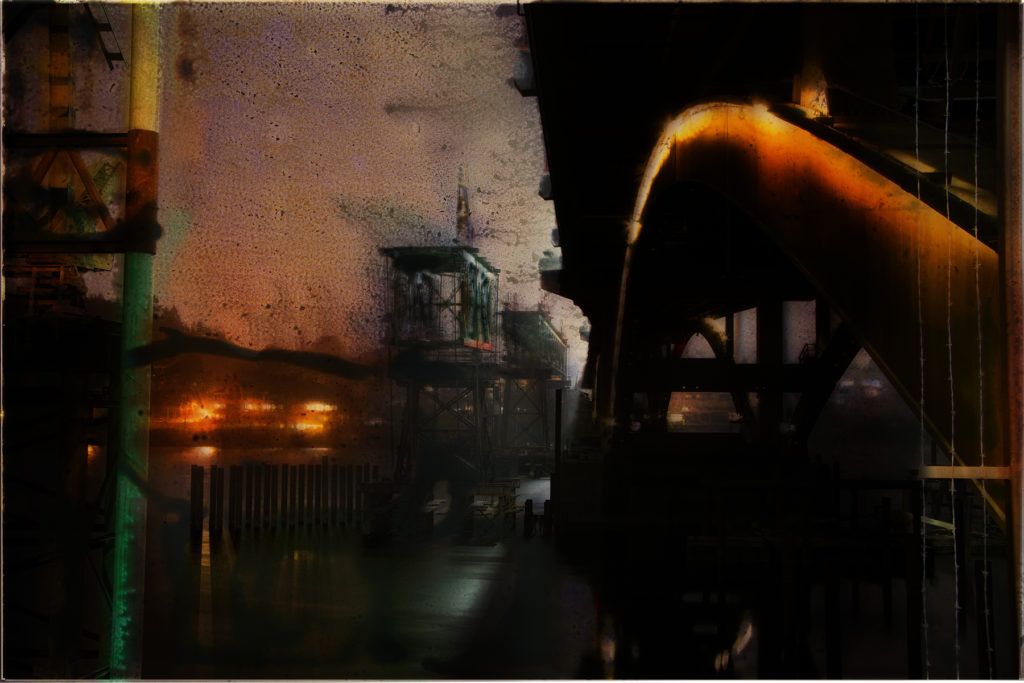

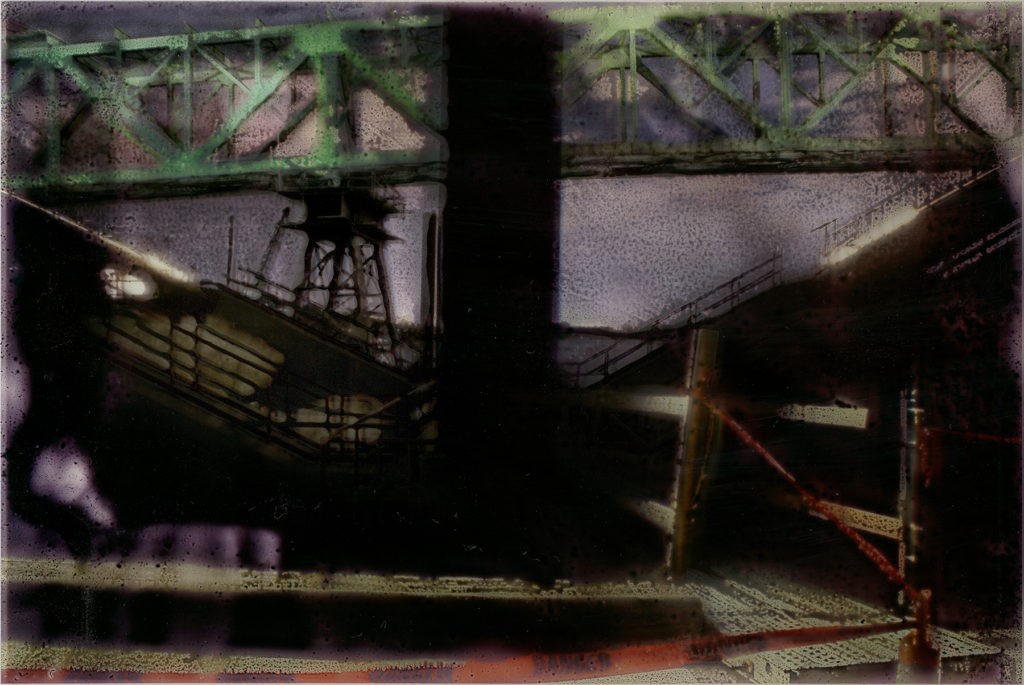

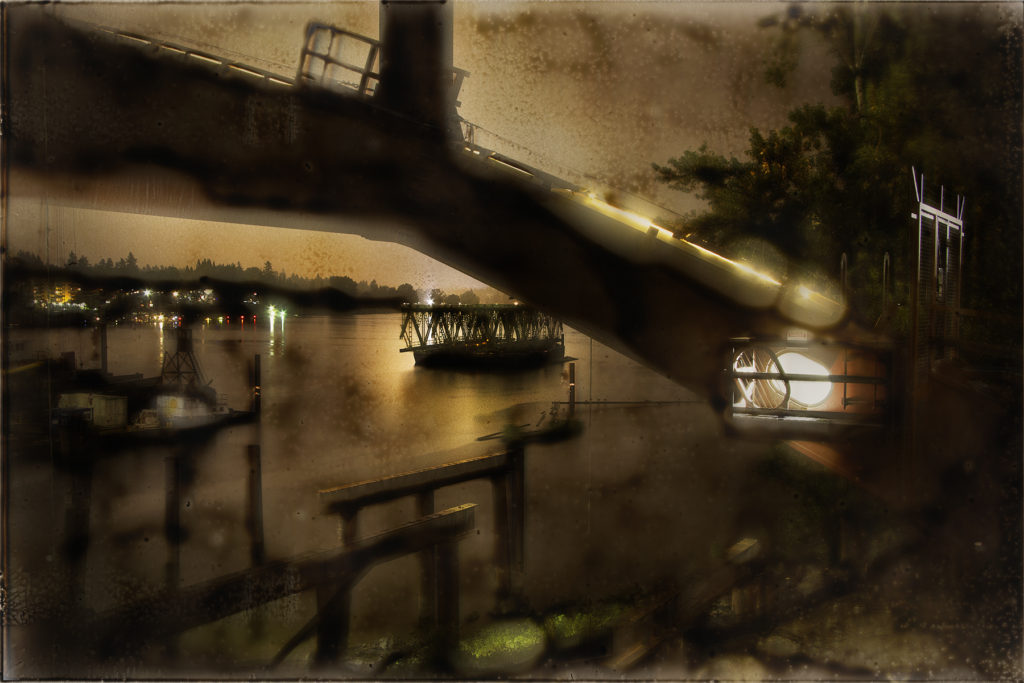

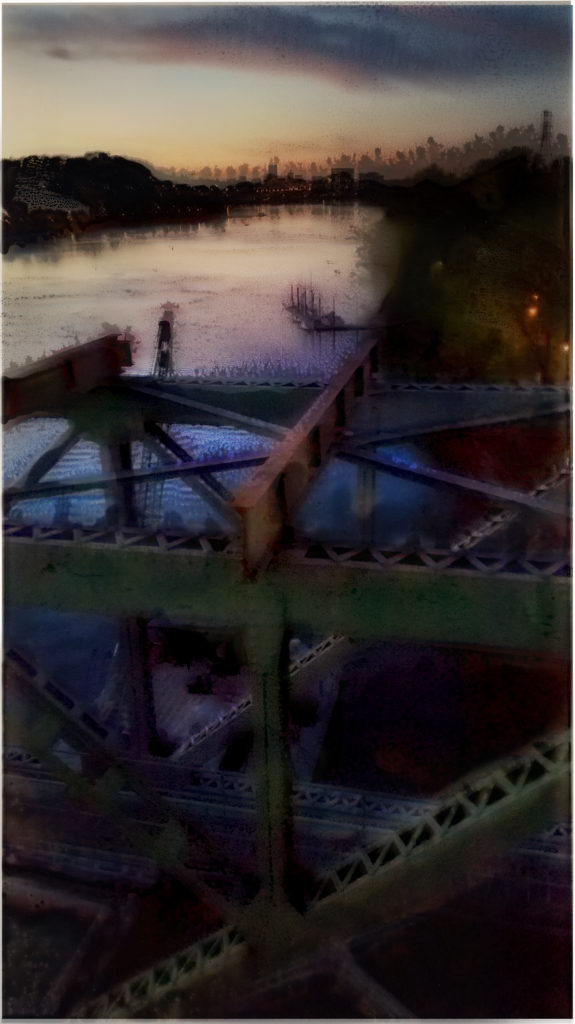

The Sellwood Bridge is Portland’s southernmost Willamette River crossing. The old span, built in 1925, was a narrow, industrial-era structure. High up on its piers, it nevertheless had an uncomplicated, slender beauty as it angled through the trees of the river’s west bank.

We’ve known the old bridge was doomed for a long time now. It was never anchored to the bedrock when it was built, and as the western bank shifted, the bridge went dangerously out of plumb. In the time I’ve lived in Portland, the bridge went from handling trucks, buses and cars, to just buses and cars, and finally, only cars were allowed over.

Plus, its narrow sidewalk was a terror to every cyclist and pedestrian who had to meet halfway across.

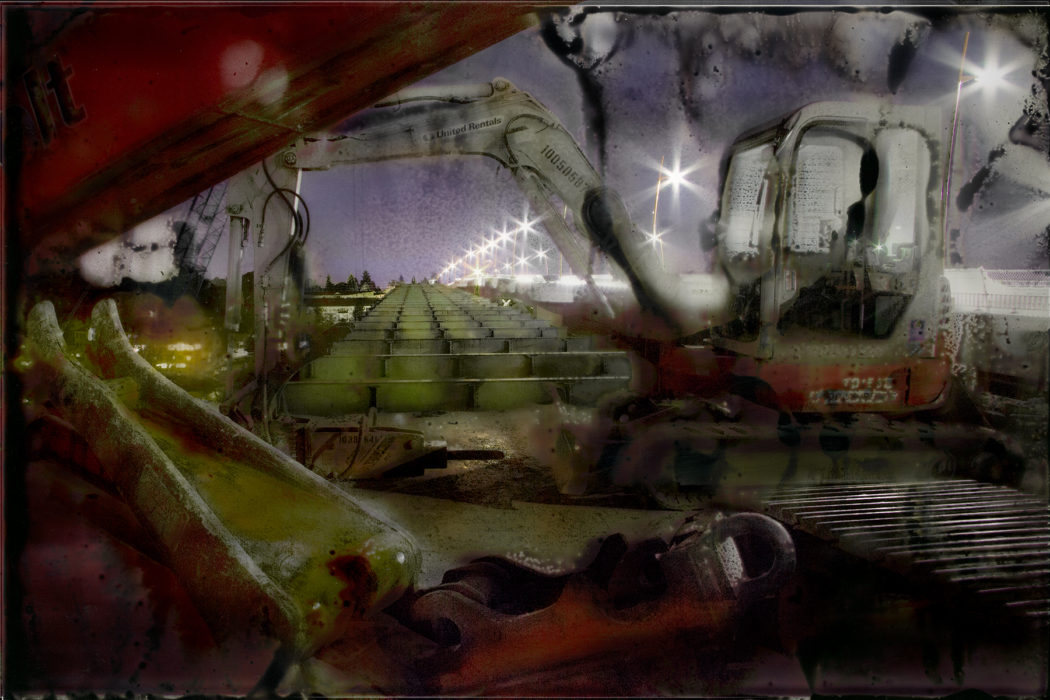

Knowing its days were numbered, I began to photograph it. Working at my favorite time to think visually—after 10pm—I became intimately familiar with this broken giant.

Today, the old bridge is now almost completely gone. Replacing it is a new, graceful arch span. There are sidewalks on both sides, wide enough for bikes to have their own lanes. Although it is more massive in every dimension than the bridge it replaces, the arch suspension makes it seem lighter, crossing the river in three graceful,LED-lit leaps.

Photographing this transition, of new bridge going up and old bridge coming down, has been an exercise in nostalgia and fascination. The exposed contrasts in technology and design encapsulate the change from then to now: 1920s young Portland, when Sellwood was a growing edge community necessitating a Model-T scaled bridge, to now, when most commuters who drive across come not from neighboring streets but neighboring counties.

My goal in these images in not just to document, in as visceral a way as I can, the size and scale and detail of these structures, and to highlight their contrasts while they co-existed, but to use the photographs as the first step in a creative process. Starting with the photograph itself, I print onto clear, non-absorbent mylar, which allows the ink to remain viscous. It moves and pools or stays distinct according to its own conductivity. I then scan the “wet” images and incorporate them into the original photograph. The variability that results is an organic addition to the digital process, which I find an immensely interesting form of inquiry.