Unreliable narration by Leo Daedalus

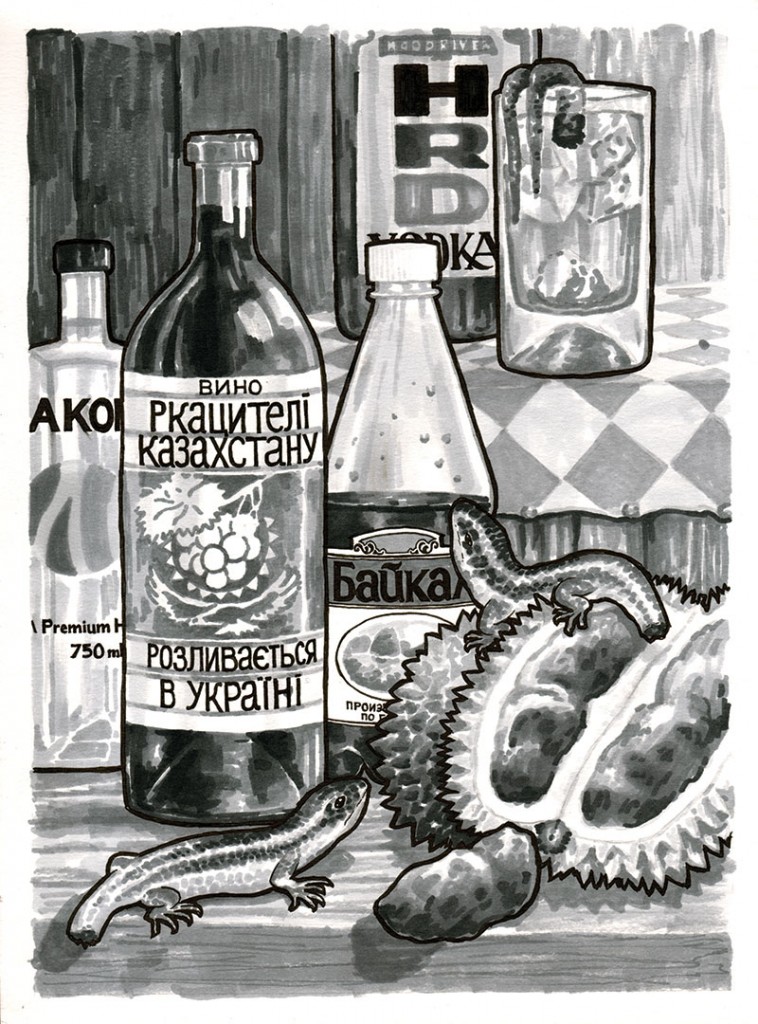

Illustration by Ezra Butt

The Thiasus is the world’s ultimate drinking competition, a kind of international ethanol rally. Every year it brings together the best and worst of extreme sport, sybaritic excess, and covert operations. And the crazy, compulsive, cast-iron people who think they can handle it. It’s senseless. It’s deadly. It’s beautiful.

Each competitor wears a SCRAM-2 bracelet that relays real-time blood alcohol and other vitals to Thiasus control in Reykjavik. When the SCRAM-2 glows blue, sleep is allowed. At red, you snooze, you know the rest.

Last time, your unreliable narrator and his drinking partner, Kati Pellonpää, were drinking jet fuel when the airplane carrying them—the ultra-rich private flying bar White Collar—was sabotaged in mid-flight by the Russian team of Vyacheslav Yerofeyev and Svetlana Terekhova. When last we left our heroes, they were passed out in the front section of the plane, in free fall.

* * *

The first thing I felt was the cold. And the hard. I seemed to be supine on an ice slab, a damp sheet clinging to me. The place was pitch black. Or no: in time I registered a dim amber tinge to the air. As my eyes adjusted, the color suddenly changed. I raised my arm. The LED on my SCRAM-2 had just gone red: the keep awake signal. I had dodged disqualification by a matter of seconds.

I sat up stiffly, aching. Machines somewhere made a distant hum. I turned my head and saw an amber dot a few feet away. I swung off my slab and lurched for it, crashing to the floor and bringing a clattering IV apparatus down on top of me. Kati bolted awake, gasping “Mitä tapahtuu?”

“Morning, sunstroke. Check your SCRAM.”

“Amber,” she said. “Vittuperkele.”

“Pretty much.”

Ten minutes later we were sitting on our stainless steel slabs like cadavers on a union break, under the bleak buzz of a single fluorescent tube. The room was cluttered with empty things: cabinets, canisters, first aid kits, pill bottles, ammo boxes, all labeled in Cyrillic. Some Kazakh. Lots of Soviet-era Russian.

The door was locked. We sat sucking the isopropyl out of a stash of alcohol swabs we’d found in a drawer, peeling and spitting them out like edamame. Limbo to Reykjavik: we’re still in the game, wherever the hell we are.

Someone outside fiddled with the door lock for far too long. Cursing happened. The door relented and a pair of uncommitted would-be badasses in fatigues entered, followed by a small, bright-eyed man in a grey suit, red tie, and dingy lab coat.

“Daedalus! Pellonpää! Thiasus!” shouted the man as he rushed over to shake our hands. “Are safe! Are happy?” Kati and I looked at each other. We looked at him. “Dr. Kazhegeldin,” he said, patting himself on the chest. “Nurlan you call me!”

Dr. Kazhegeldin noticed the alcohol swabs and laughed himself silly. Even the hench-guys thought it was funny. Teary-eyed and still giggling, he shouted, “Come! Drink!” He shook our hands all over again.

Upstairs in his office, he gestured out a greasy window and exclaimed, “Zyryanovsk! My city! You see smoke over there? Dry cleaner is explode! Your fault!” He laughed and handed us a couple of full glasses. “Now you drink Baikal Highball!”

The Baikal Highball

1 part Kazakh Rkatsiteli wine

1 part Baikal, the Soviet answer to Coca-Cola

various parts vodka impurities

“When I was kid, my father sometime get black market Coca-Cola. But to me Baikal is right taste. Nostalgia!” He raised his glass. The hench-guys were drinking too. They started bickering about Coke and Baikal. “OK. Now we hurry!”

Drinks in hand, we were rushed downstairs, out the building, and into a battered UAZ-469 that looked as if it had been driven to Zyryanovsk from Mars. The good doctor took the wheel, tour-guiding us incomprehensibly as we rattled through the city. Everything he said seemed to be about what used to be there back in the day, and mostly it was drinking joints that were better than the ones that replaced them.

We turned the corner into a crime scene. A building lay in smoking rubble. A cordon of uniforms stood around nervously clutching rifles while a handful of government types in leather coats smoked, pointed, and drank. Kazhegeldin took us around the scene, cheerfully greeting everyone he knew there, and he knew them all.

“All this your fault!” he said, laughing heartily. He intercepted one of the leather-coats’ bottles and we traded swigs while he tried to explain. It took a couple of bottles before we could piece the story together.

The White Collar front-section “lifeboat” had parachuted safely into a field outside Zyryanovsk. Ettore Piavoli made arrangements. Kati and I were carted off to the hospital, while Ettore and his high-rent pals got out of Dodge one way or another. In the meantime the White Collar tailor had stopped off at the dry cleaner, impeccable chap that he was. And then, the dry cleaner was hit by something nasty. Probably a Scud.

“What does it have to do with us?” Kati asked.

“You?” Kazhegeldin twinkled. “How do I know? Simply you are trouble. Everything your fault!”

“He’s right,” I said. I told them about my bump-in with what was probably an FSB agent back in Los Angeles, at It’s Complicated, about how she held my sleeve a little too long. “That’s why the Russians were always one step ahead of us.”

“A tracker,” said Kati.

“Da. But they didn’t know I’d had a costume change in White Collar. My old suit must have ended up here.”

Kazhegeldin roared with laughter, “Now you never get stain out! OK! We go!”

“Wait,” I said, and headed into the rubble. The back of the building was still partly standing, and I poked around until I found what I was looking for. I emerged with a solvent tank of dry-cleaning fluid. Perchloroethylene. Perc. “OK. Where to?”

“You go Mongolia,” said Kazhegeldin as we jumped into the UAZ-469. He drove us to a military airfield, explaining on the way that the Mongolian prime minister’s brother was a fan of the Thiasus, and had taken an interest in our cause, but that we hadn’t heard it from him. We drove right up to a Mil Mi-24 helicopter, rotors spinning. Kazhegeldin handed Kati a cumbersome sack as we boarded. “Kazakh pomegranates! Good luck!” We strapped in, donned headsets, and the copter rose as Kazhegeldin waved from the tarmac.

Kati looked at me. “Since when does Thiasus involve major collateral damage? This is serious.”

“And it’s not like Vyacheslav and Svetlana,” I mused. “They play hard, but never like this.”

The copilot turned around and tapped a flatscreen monitor mounted in front of us. He gave us a thumbs up. I hit the switch. It was the live feed from Thiasus control in Reykjavik. As we watched the play-by-play, we muddled pomegranate seeds into metal cups and stirred in dry-cleaning fluid. We watched our spikes on the Reykjavik feed as the perc hit our bloodstreams. Solid work.

The Colorless Pomegranate

freshly muddled pomegranate seeds

perchloroethylene to taste

last will and testament

But we were screwed. Everybody had bailed on us after we dropped out of the sky. Even Ettore had moved his bets. Strangely, though, the Russians were also bottomed out. All the money was between the Irish and Swiss, the only other contenders still standing. The Irish? How had they gotten this far? They were hardcore, no question. But every year they took the wrong nap at the wrong time and that was all of that. And the Swiss? They played an exact game and inevitably made it to the end, but always just a degree too sober. Go figure. This was shaping up to be the weirdest Thiasus ever.

There was of course one other team. The Mormons. They played every year—every year dead last and bone dry. But cheery as hell. Their annual losers’ victory speech was a Thiasus highlight, the perfect drinking game. The Mormons, thankfully, were still behind us.

We watched western Mongolia roll out beneath us as we sped east, sipping our perc and juice, kicking back. It’s when you should be worrying most that you should worry least. Truth is, this was the life. Soviet copter, fresh pomegranates, dry-cleaning fluid, time on our hands.

The copilot turned to face us. “Distress signal,” he said, pointing straight down. “We go.” And we did.

We set down in the dead center of nowhere, neatly bisected by a dirt road that crossed straight from nil to niente, horizon to horizon. And in the middle of that lay a military truck, sprawled out on its side next to a bomb crater. In the truck, four bodies. We watched as pilot and copilot jammed open the doors and hauled them out. Two of them were young soldiers, drivers. The other two were Svetlana and Vyacheslav.

Kati and I, leaning in the shade of the copter, did the only thing we could do. We drank.

TO BE CONTINUED

Friend, the Thiasus never goes as planned. Sometimes less, sometimes less still. This is one or more of those times. In vino veritas is not a statement about factual truth, much less arithmetic precision. What does a word like “trilogy” really mean? “Story in three parts?” What’s in a number? Ask the anumerate Pirahã people of Brazil. They don’t care. Drink enough cachaça and you won’t either. That’s not a rhetorical observation, it’s a direct order. Go. Drink! And then, look forward to the next installment of Thiasus: Part 4 of 3, the exciting conclusion—probably.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *