By Ezra Sandzer-Bell

It is the dead of night and silence permeates the cityscape, interrupted only by the occasional exhalation of a distant train. Ambient moonlight pours into bedroom windows. An ambulance races down the street, wailing like the sirens of ancient Greece.

Philosophers used to gaze into the heavens on nights just like these, imagining a world of sound long before the advent of orchestral music. They watched patiently as each planet journeyed around the sky in orbit. The cycle of each astral body created a distinct musical tone, like fingertips along the rim of a wine glass. If you could hear them all together, the planets would have resonated with a sweet celestial harmony.

Science has demonstrated that the pitch of a musical tone is determined by the frequency of acoustic wave-cycles per second. This same knowledge was taught in the secret societies of ancient Greek civilization, framed in an astrological context called the Harmony of the Spheres. Sound waves were represented by planetary orbit all the way through the Middle Ages and Renaissance period, as a layered hierarchy of celestial beings extending from Earth to Heaven. According to tradition, before and after death each human soul journeyed through these layers and absorbed the planets’ vibrational essences.

The famed Greek philosopher Plato wrote one of the first recorded documents of such celestial music in his book The Republic. Near the end of this book, in a story called The Myth of Er, Plato describes the death of a warrior on the battlefield. As the warrior leaves his body, he discovers himself surrounded by the souls of other dead soldiers. He ascends to the sky and is brought to a meadow, where he is introduced to a rainbow pillar of light and receives initiation into the fabled Spheres. Each planetary body in the solar system was mounted by a winged maiden called a siren who rode the orbital circuit of her native planet endlessly while intoning a musical pitch unique to that region of the solar system.

In some Greek myths, sirens appeared as mermaids who lured sailors to the shore of an island with their song, only to murder and devour the innocent mariners. Ancient people regarded siren songs as seductive and deceptive, promising pleasure but ending in cannibalism. Today, cop cars and ambulance sirens still trigger these mixed associations of salvation and danger.

Not all musical spirits were depicted as dangerous, however. Proclus, a philosopher from the 5th century AD, made an important distinction between sirens and the muses, explaining that the latter were beneficent spirits responsible for inspiring humanity’s creative musical activity. Guiding these muse figures was Apollo, a patriarchal figure who valued beauty and worked tirelessly to bring musical harmony to Earth.

Apollo was one of the original singer-songwriters. He performed on a stringed instrument called the lyre, which he acquired from one of the great liars of the Greek pantheon, Hermes. According to legend, Hermes defied Apollo and stole a group of cattle with the intention of harvesting their organs. Leading the heifers to a cave, he discovered a tortoise that he murdered and harvested for its shell. With the cows’ intestines he created musical strings, and by fastening the cattle guts to his hollow turtle shell, Hermes produced the first instrument of its kind. When Apollo discovered what Hermes had done he was furious, but Hermes coaxed Apollo from his anger with a skillful performance upon the lyre. Hearing the instrument’s beautiful music, Apollo agreed to surrender the stolen cows to Hermes in exchange for the instrument.

The Roman name for Hermes was Mercury, the resident deity of that same planet. It is a little known fact that the orbital length of Mercury is 88 days, identical to the number of keys you would find on a standard grand piano today. As a “messenger of the gods,” Mercury watches over the arts and mediates between human and godly realms, guiding individuals through the creative process. His signature magical weapon, a winged staff called the caduceus, is said to transmute suffering into blessings. In modern times it has become a standard symbol for Western medicine. The placement of the caduceus on ambulances doors contributes an added layer of astro-musical significance to the wavy slide-whistle tone of its siren.

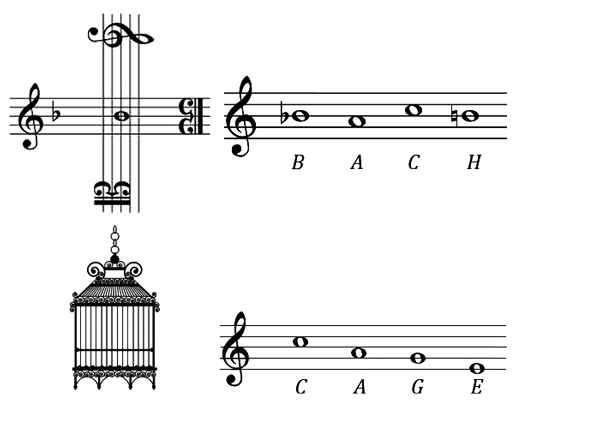

In Germany, the musical note B natural is written as “H” and the note B flat is written as “B”. The two top graphics are a musical pun and cryptogram written by J.S. Bach called the “Bach Motif”, spelling out a four note melody from the four directions. The differences between notes are indicated by the position and key signature of the Alto and Treble Clefs. One could produce a similar melodic motif with the last name of American composer John Cage as shown in the bottom right graphic here.

Consider for a moment that Greek Hellenistic astrology conceived of only seven planetary bodies in relation to Earth: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. If Mercury was intended to be the patron deity of the piano, perhaps the seven notes of the white keys signify those planets. The additional five notes of the black keys could represent the night sky, or alternatively, you could sum up the seven white keys and five black keys to arrive at the number twelve, which is congruent with the number of signs in the tropical Zodiac. In this way, the myth of the Harmony of the Spheres would have been preserved in the very structure of our musical instruments and chord formations.

The passage of time plays a critical role in both astronomy and music. The twelve months in a year relate to the twelve hours in a day, indicating long and short scalar measurements of chronological time. All of the common Western instruments, including piano and guitar, are built upon a base-twelve tuning system. The use of twelve notes implies a method of measurement similar to that utilized for our clocks and calendars. Though they are not literally measurements of musical rhythm or note duration, the twelve notes equally subdivide an octave the same way that the twelve zodiacal signs subdivide the sky. These twelve notes become the basis of both major and minor chords, which signify the energies of day and night respectively. The twelve major and twelve minor keys seem to relate to one full day-cycle of 24 hours, while the notes by themselves imply the zodiac.

To be fair, explicit influences of Greek mythology and the Harmony of the Spheres upon Western music have gone largely undocumented, so the true symbolic meaning of the piano stays open to interpretation.

The Collapse of W.T.C. I and II . A Mega-Ritual of the Musical Apocalypse

Historians tend to regard German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) as the father of Western classical music. Bach had the foresight to compose two books featuring 24 songs each, called the Well Tempered Clavier I and II, written in the twelve major and twelve minor keys. At a time when there was still no universal tuning standard for European instruments, Bach’s music successfully persuaded composers and instrument builders to choose twelve-tone equal temperament over myriad alternatives. WTC I and II have since become major pillars of musical thought in the Western canon, analogous to the twin tablets of the biblical Ten Commandments.

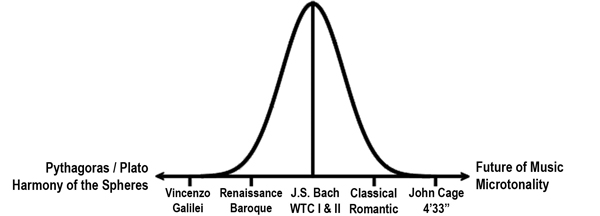

Roughly 200 years prior, the Italian astronomer and luthier Vincenzo Galilei (father of the famous astronomer Galileo) assembled one of the first collections of 24 musical pieces, loosely related to the idea of twelve major and minor keys. However, these songs were not nearly as influential as the WTC, and few people today are aware of Vincenzo’s existence, let alone his musical repertoire.

Imagine a 400-year bell curve, beginning with the birth of Renaissance music theorist Gioseffo Guami in 1542. Guami was a key figure in Vincenzo Galilei’s musical worldview. This hypothetical bell curve rises through the Renaissance and Baroque periods of music, peaking during the completion of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier II in 1742. From here the line dips back down through classical, romantic, and modern music.

The present day musical situation on our planet is kind of bizarre. In its maintenance of the 12-tone system, pop music remains tethered to an astro-theological musical idiom that was rendered obsolete over half a century ago, when revolutionary American musician John Cage boarded a plane from Chicago to New York City in 1942. Many of the techniques developed by Cage during his residence in NYC have since come to represent a Ground Zero in Western musical thought. Contrary to the carefully procured classical methods of voice leading and harmony that made Bach famous, Cage relied on chaos and random processes of chance to compose his music.

Cage consulted the I Ching to determine things like rhythm, dynamics, and tone sequences. Later in life he applied similar methods to the interpretation of astrology charts in his pieces Atlas Aclipticalis (1961-62), Etudes Australes (1974-75), Freeman Etudes (1977-90), and Etudes Boreales (1978). The idea of using Chinese divination to compose music would have been heretical during Bach’s life. A hired composer never could have gotten away with it. Things loosened up in the following decades when Mozart wrote a piece of music called “Musikalisches Wurfelspiel,” which translates to “Musical Dice Game.” The melodies of these songs were based on the roll of dice, a variation on what Cage called the chance operation. But of course, Mozart’s intention was geared toward the amusement of a Freemasonic bourgeois, rather than the dissolution of their ideals.

A harbinger of the Western musical apocalypse, John Cage’s flight to NYC in 1942 may as well have crashed directly into WTC I and II. During his career, he stuffed objects into piano strings and instructed composers to play outrageous tone clusters with their forearms. Ten years following his arrival in the Big Apple, having effectively demolished everything that Western music supposedly stood for, Cage composed his trademark composition 4’33, a carefully timed piece that calls for three distinct movements of silence in various lengths. Performed in massive concert halls around the world, the absence of music in this performance was received by audiences as a joke, an insult, and a prayer all at once. It also seemed to symbolically demand a new era of music.

In a famous video interview from 1991, Cage notes that his favorite thing to listen to is the sound of passing cars on city streets.

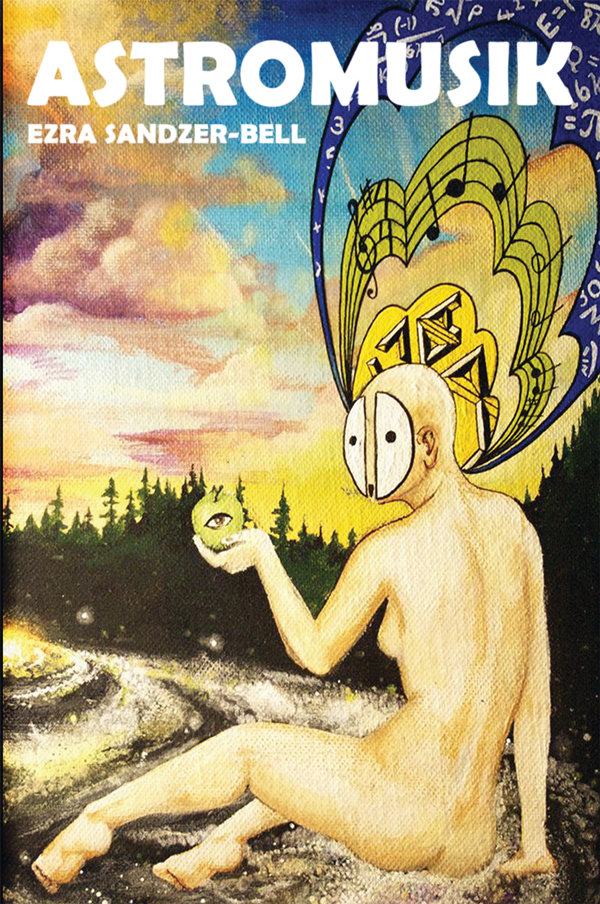

Ezra Sandzer-Bell

is a musician and writer based in Portland. He is the author of Astromusik: Tone Color Alchemy, published April 2014 by Sync Book Press. His website is tonecoloralchemy.com, or contact him by email at

tonecoloralchemy@gmail.com.