Unreliable narration by Leo Daedalus

Illustration by Ezra Butt

So here I am, backroom of the Sidetrack, nursing the mother of all freeze-distilled Kumis hangovers with a lukewarm can of Pops Blue Father, the weakest beer modern science can brew. Must be two in the afternoon, or in the morning, or six p.m., or something like that. Vyacheslav Yerofeyev is slumped in the corner on a drift bank of damp sawdust brightened with a few drops of blood. I don’t remember if he’s dead or just sleeping it off. I don’t remember much, but I’ll try to wind it back for you.

It started here, what—five days ago, let’s say. Days. Nights. Who knows? Kati and I were peeling back PBFs by the six-pack and drawing diagrams on bar napkins. That’s Kati Pellonpää, the best in the game. She’ll drink the table under the table. You always want a Finn or a Russian on your team. I worked with a Russian once. Things got partisan. Cleanup was a headache. So I stick to my Finns. Six years running, I stick to Kati.

So. We’re diagramming our attack plan for the Thiasus, marking up napkins and drinking Pops Blue Father. Drinking? PBF isn’t drinking. This is pre-warm-up, Limbering up the esophageal tissues for the work ahead. This is my thirteenth Thiasus, Kati’s sixth. I discovered her. She was just a kid, really, and the only one left standing in an arctic baari full of beefy, passed-out foresters outside of Rovaniemi, one ink-black December morning.

The Thiasus is the world’s ultimate drinking competition, a kind of international ethanol rally. Every year it brings together the best and worst of extreme sport, sybaritic excess, and covert operations. And the crazy, compulsive, cast-iron people who think they can handle it. It’s senseless. It’s deadly. It’s beautiful.

We knew there was only one team to worry about: Vyacheslav Yerofeyev and Svetlana Terekhova. The Russians. Everybody else would take care of themselves. Lucky for us, we had a jump on the Russians: we knew this year’s praetor, and we knew his kryptonite.

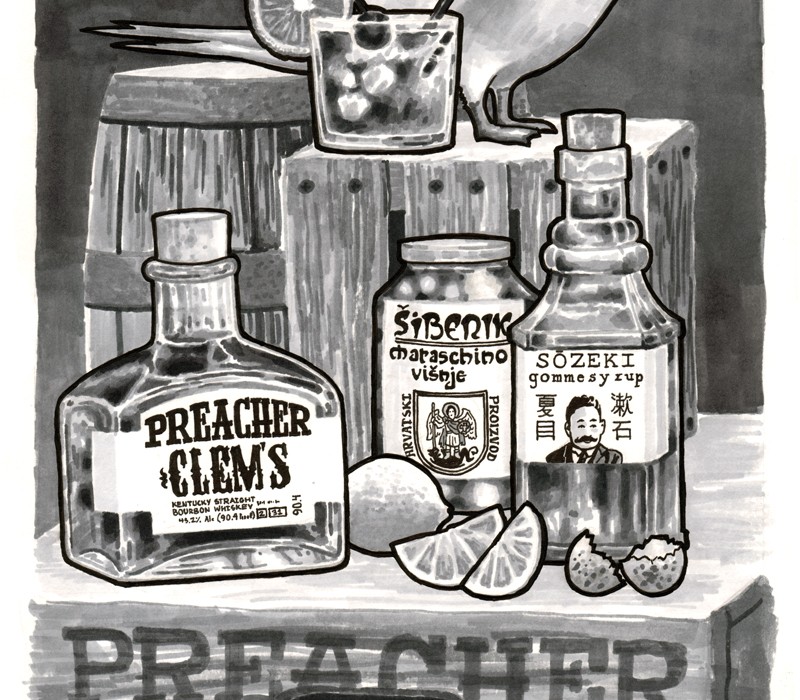

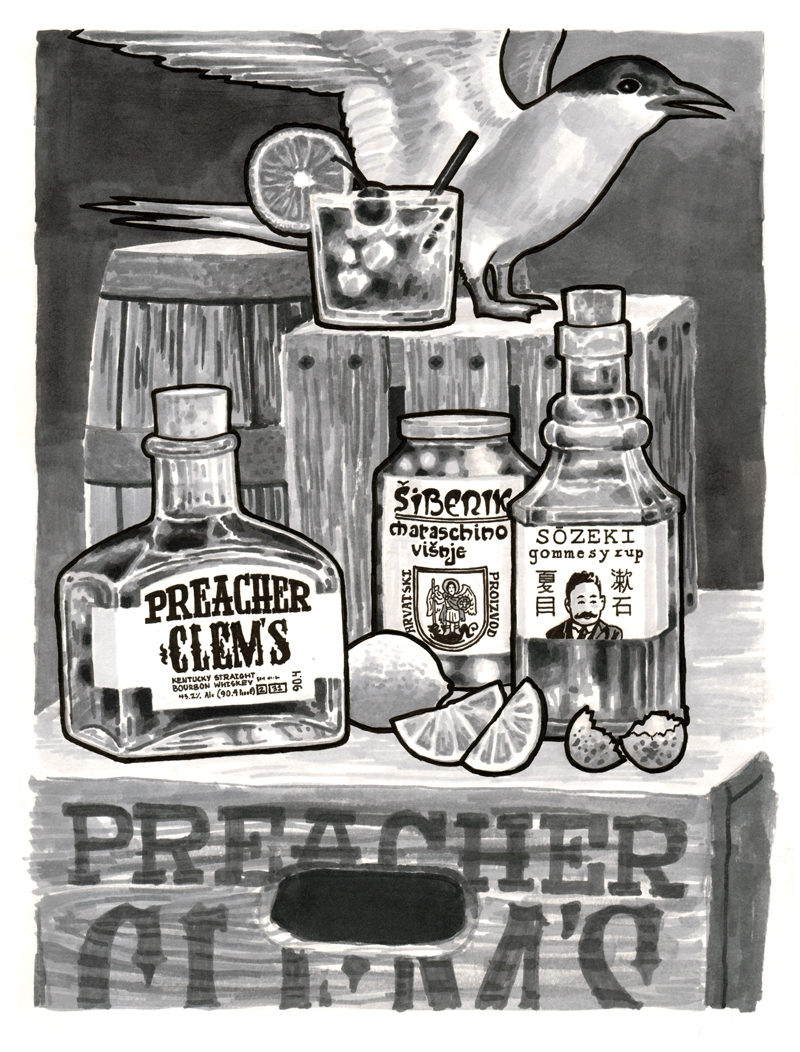

The Praetor Kryptonite Whiskey Sour

Adriatic seawater rinse

45ml Preacher Clem’s bourbon (2 barrels produced annually)

30ml fresh Yen Ben Lisbon lemon juice

15ml Sozeki Gomme syrup

One dash Arctic tern egg white

Šibenik maraschino cherry

A handful of these was enough to get two words out of him: “It’s… Complicated.” That’s why he doesn’t compete. It’s Complicated is a Los Angeles breakup bar catering to the social anxiety set. It’s so dark in there raccoons lose their drinks. Night-vision goggles strictly prohibited. Kati, who spends half the year in the heart of Arctic darkness, couldn’t care less. We slithered up to the bar and ordered the only drink It’s Complicated serves:

The By Any Means Necessary

alcohol (to taste)

mixers (optional)

We mingled. We asked the right questions. We avoided the civilians (anyone crying). Eventually the right Benjamin slipped into the right fingers and a man calling himself Casares slipped us out the back and into an Escalade. But by then I think we were already compromised. A few minutes earlier I had bumped into someone and there was a bit of a stumble. A Russian-accented female voice apologized and held my sleeve a bit too long. The whole thing had an FSB feel to it.

Casares drove us east. We drank Cuba Libres with bootleg Nigerian Coke—the stuff with a hint of antifreeze—to keep the momentum. He took us into a long defunct gasworks or chemical plant, into which labyrinth we penetrated until we heard the unmistakable sound of multiple cocking 12 gauges. “Quo vadis, y’all?”

So this was the Still, a Thiasus legend. Casares made the right noises and we were in. A man named Caleb (seriously?) led us to the apparatus. I tripped on a body: Enrique, one of the Spanish team. He had a pulse, more or less. His partner, some petite Andalusian, was snoring haplessly in the corner. Amateurs. Caleb unscrewed a squeaky valve and filled a couple of chipped mason jars for Kati and me. She spit out a mouthful and hissed, “Moonshine!”

Caleb laughed a gravelly laugh, “Maybe the lady wants some grenadine with that.”

I poured mine out on the floor and said, “Enough with the soft drinks, son.”

Again with the cocking 12 gauges. “Boy,” growled Caleb, “we run this lightning through 18 feet of vintage General Motors radiator coil. Like my momma said, lead burns red and makes you dead.” Caleb was talking about the old backwoods test: if you ignite a bit of moonshine in a spoon and it glows red, it likely ran through radiator coil and has lead in it. Bad stuff. In Thiasus terms: the jackpot.

All Thiasus competitors wear a next-gen SCRAM-2 bracelet sensitive enough to detect the composition of your last cocktail, down to the brand of pimento. The data continuously stream to the control center in Reykjavik. By “control center,” of course, I mean “gambling den.” You do have to cross the finish line, but the Thiasus is all about the journey. This is why 18 feet of vintage General Motors radiator coil is worth so much to a serious player.

“That’s sweet, Caleb,” I said, “but you know damn well why we’re here.” Casares made his excuses and vanished. We stood in silence. “Foreshot,” I whispered. “Now.” The foreshot is the first few ounces of moonshine that drips from the distiller. It contains most of the methanol, plus a few other sweet nasties like acetone and various aldehydes. It’s a disaster. Guaranteed to spike our SCRAM-2s. Caleb started to make excuses. Suddenly we heard Russian shouting somewhere outside the compound. “Now, Caleb!” Kati flashed a few ounces of gold—‘shiners like glittery things revenuers can’t track—and Caleb, with a nervous glance at his gunmen, pulled us into a back room.

“This is all I got.” Caleb pulled a soiled handkerchief off a jar with about six fingers of real bad liquid. The Russians were nearing. Kati grabbed the jar, swigged an even half, and shuddered convulsively. The door flew open and Vyacheslav tackled me as I downed the rest.

My eyes rolled back into my head and I almost passed out with Vyacheslav yelling “Все заебало!” into my face. Almost passed out, but didn’t. This is key. The Thiasus has strict rules about how and when you can be unconscious. Passing out from drink is game over. Kati pulled Vyacheslav off me. Svetlana was checking every vessel in the place. I pulled Caleb to me and whispered, “Recyclone. More gold.”

The rest is vague. Somehow we made it into a freight elevator, with the Russians still yelling at Caleb’s heavies. Caleb made Kati and I put on headbags. I protested, “It’s an elevator. What’s to not see?” Caleb punched me in the gut. Or I did. Or something.

When the headbags came off what seemed like half an hour later, Kati and I were standing in an immense industrial cavern filled with a giant makeshift funnel, all rivets and rebar. A shrieking din of breaking glass assaulted us, deafening and constant. Kati, the least expressive human being on the planet, dropped her jaw and whispered, “Paskanmarjat.”

Recyclone may be the harshest drink on the planet that won’t just kill you outright. Worse probably than the Vladivostok diesel I survived in ’08. My buddy Hakan in the Turkish National Intelligence Organization told me about Recyclone the year I had my liver transplant. I knew that if I ever made it to the Still, this was the next step.

Recyclone is the project of two brothers from the Portland Vegan Mafia, a couple of hardset anarchomothers who got driven out of Oregon a few years ago and set up shop in an undisclosed location we now know to be somewhere east of Los Angeles. One has a beard, the other dreads. No one knows their real names. The PVM runs all the recycling depots on the West Coast, and the brothers work it so that all the empties from San Ysidro to Point Roberts end up in their funnel. Every drop, every smudge of booze residue drips down the works, through the glass filters, and pools into an infernal gray cocktail of undead spirits. The smell of the place.

Two dudes with mirrored cat-eye glasses approached us. One had dreads, the other a beard. Dreads spoke: “Ms. Pellonpää, Mr. Daedalus, it’s a privilege. May we propose a toast?” He handed us each a tumbler. “Professionals take it neat.”

My friend, words fail me. That Vladivostok diesel martini I had in ’08 was Jura Vintage ’77 Scotch in comparison. This was like sucking on a Hieronymus Bosch painting in the backseat of a cesspool truck while going down on a pack of hot polecats. With strobe lights. I think I had a seizure. Kati, even, was on her knees. “I know what happens next,” she groaned.

Dreads grinned and said something about a job he wanted us to do. I muttered something about the Russians. He waved dismissively and said, “You got here first.” Then they were strapping a bushel of C-4 around my torso and swaddling me in Kevlar. I saw my SCRAM-2 LED turn blue: the OK signal for bedtime. I let myself go unconscious.

I drifted awake in the shuddering hold of a cargo plane. Kati handed me a flask and a satphone. “We land in Naples in 50 minutes. Drink. Call the police.” I did. My SCRAM-2 was still blue. Out I went.

Eventually there were sirens, leg irons, steel doors, lots of Italian. No sign of Kati. When the haze cleared I was sitting on a lower bunk in an Italian prison cell. I felt a hand on my shoulder. “Привет, Daedalus.”

Oh God. Vyacheslav. My new cellmate.

TO BE CONTINUED