Unreliable narration by Leo Daedalus

Illustration by Ezra Butt

The Thiasus is the world’s ultimate drinking competition, a kind of international ethanol rally. Every year it brings together the best and worst of extreme sport, sybaritic excess, and covert operations. And the crazy, compulsive, cast-iron people who think they can handle it. It’s senseless. It’s deadly. It’s beautiful.

Last time, this unreliable narrator and his drinking partner, Kati Pellonpää, outmaneuvered the Russian team of Vyacheslav Yerofeyev and Svetlana Terekhova to get a drink of Recyclone, the stuff of legend. When we left our heroes, Mr. Daedalus had just awoken in a Neapolitan prison cell, along with his Russian arch-rival.

* * *

“Looks like we are in next round together,” said Vyacheslav. We and a couple of heavy Camorra malviventi mouth-breathing on the other bunk.

I smelled something dank, sickly fruity, that I hadn’t smelled since Johannesburg ’05. “Oh, no,” said I, giving Vyacheslav a look. “Da, droog,” said he, grinning. Pruno is a prison wine made of anything with sugar content: fruit, ketchup, milk, you name it. That’s what they call the motor. Add a little crumbled bread for yeast, some water, and heat, and eventually you’ll have a cloying, vomit-flavored rotgut with just enough buzz, hopefully, to help you forget the taste. The really bad stuff is fermented in toilets. The worst in the world, the stuff of legend, is said to come from Neapolitan prisons. Vyacheslav informed me that our Camorra pals, Beppe and Paolo, were reputed masters of this desperate art. Kati had done her homework. The Russians had too. Although on the scale of coincidence, this certainly had the tang of enemy action rather than happenstance.

With a flourish of incongruous grace, Paolo lifted the lid from the toilet tank. The smell weighed down the room. Beppe handed Vyacheslav and me each a battered tin cup. We dipped. “Za vas!” We drank. We gagged. After the Recyclone, it was nectar of the gods. Things were looking up. Vyacheslav and I matched each other tin cup for tin cup until the tank was drained. We entertained each other with reminiscences of Thiasuses past. The Italians cheered us on. Eventually I fixed Vyacheslav with my piercingest stare, which by then was a dampened myopic wobble, and I said, “Now tell me, how the hell did you wind up in here with me?”

Vyacheslav checked his watch. “Oh, look at time. I expect visit from Svetlana. Cover your head.”

There was a blast, lots of dust and coughing, and the four of us picked our way out through the rubble. Svetlana greeted us with a bottle of nameless potato vodka from a farm outside Smolensk. I took a swig. She looked me in the eye, smiled, and said, “And now, we will bury you.”

With a screech of tires, Kati pulled up in a Lancia Stratos—hot, no doubt—and tossed me a bottle. “Have some real vodka,” she said. Finnish vodka. I recognized the precise bite from a still the locals call the Sammas, out in a godforsaken corner of Kivikonsaari, an island just off Karstula. I saluted the Russians and climbed in. We hit the E45 and made for Vesuvius at top speed, trading swigs. Don’t try this at home, kids.

“I take it our job for the Recyclone boys paid off,” I said. Kati nodded. “What’s a little gun-running among friends?” Kati nodded again. You don’t go to the Finns for chit-chat. “And now, let me guess. Vesuvius means Ettore Piavoli’s private airstrip outside Boscoreale?” Kati nodded a third time. “White Collar, here we come!”

White Collar is one of the most exclusive drinking establishments on Earth; or, more accurately, above it. It indulges a dozen lucky guests at a time at 40,000 feet in the ostentatious luxury of a custom Embraer Legacy 600. Only a handful of people in the solar system can actually afford a drink on White Collar—except that the drinks are free. At that altitude, money is beside the point. White Collar guests are chosen; they receive notice. A rarefied breed. Their hands are never dirty, and their consciences are never clean.

We ditched the Stratos right on the tarmac. Ettore Piavoli in white suit and Mastroianni shades lifted a glass in salute from the open door of White Collar. “Ciao, bellissimi!” I was sent to the back of the plane for a fitting. My suit reeked of C-4 and toilet wine, and looked worse. While I waited for the tailor to finish up, Ettore’s impeccable mixologist-sommelier, wearing an anonymizing eye mask, handed me a glass of Bruno Giacosa Collina Rionda ’78 “to awaken the tongue.” Before I could nose it, she dropped in a pearl of freeze-dried Tongareva honey. Ettore winked. Somehow, the reckless concoction worked.

Kir Diavolo

Richardson & Sons, Stourbridge fluted baluster stem glass (ca. 1880)

Cannubi 1752 (pre-Barolo) rinse

Bruno Giacosa Collina Rionda ’78

One pearl freeze-dried Tongareva honey

Once at altitude, Ettore explained that he and his other guests, who would all remain anonymous, had their bets on us. This despite some recent surges by Svetlana and Vyacheslav. While we were hitting the Recyclone, the Russians got their hands on some chang’aa, a high-octane grain alcohol popular with Kenyan gangs, whose poetic name means “kill me quick.” I’ve never so much as sniffed the stuff. Worse though, they scored an east-Helsinki variant of kilju (pronounced “kill-you”), a nasty sugar-fired bootleg that juices up the Finnish punk scene. Kati, in a rare show of emotion, shattered the Richardson & Sons glass in her hand. But everyone agreed that the Recyclone would retain the crown.

“Amici,” announced Ettore, “we will be in Ulaangom at dawn. Mongolia, bambini!”

“Sure. What’s in Mongolia?” I asked.

“Two things,” he said with an impish tap on the nose, “that will make you a legend. But now, let’s get serious.” He clapped. The mixologist appeared with a tray of modified lowball glasses with thick, opaque bases. “This will spark your interest,” said Ettore, handing Kati and I the first two. We were shocked. Literally.

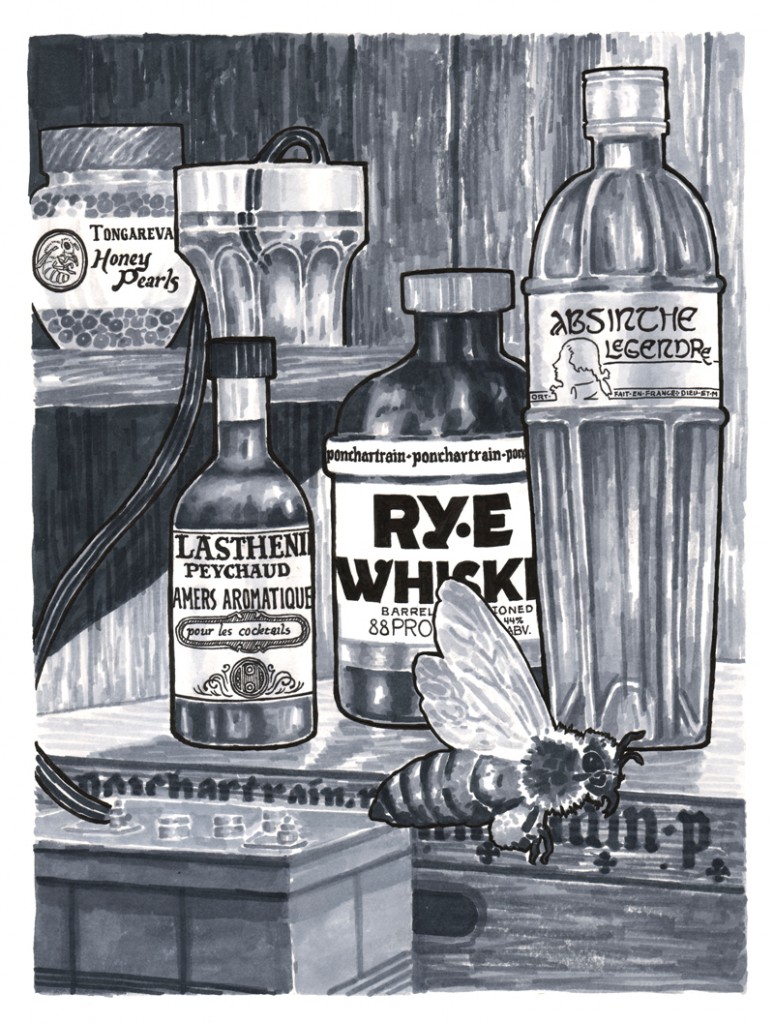

The Electric White Collar Sazerac

60ml Pontchartrain rye whiskey

Three dashes custom Lasthenie Peychaud bitters

One pearl freeze-dried Tongareva honey

One splash Grande Wormwood-infused Legendre Absinthe ’34

48-volt low-profile battery set (proprietary)

“The electric current really brings out the gentian, non è vero?” It was true. And it was only the beginning. We were just moving on to the next cocktail, a Special Tokugawa Shotgun garnished with toasted black pepper, when the copilot whispered in Ettore’s ear and handed him a pair of binoculars. He peered grimly and passed them to me. Paralleling us off the starboard side was a spritely Sukhoi Superjet 100. “The Russians,” I muttered. “Step on it. And stiff up the drinks.” My SCRAM-2 flashed blue, but sleep is for the virtuous.

The game was on. We kept the mixologist busy, surfing a tsunami of recherché potations: the Dirty Kaiser Wilhelm, the Boston Strangler, the Petronius Arbiter, the Toledo Ohio Supreme, the Mad Anglican (like a Mad Sufi but with gin), the Laudanum Gaze, the Prickly Thymus, the Double Winchester Maximum (with ouzo instead of bourbon), the Fourier Analysis on the Beach, the Madagascar Empty Helmet, the Strawberry Marshal Josip Broz Tito (up, no rocks, please), and finally the pièce de résistance, the Moscow to the End of the Line.

The Moscow to the End of the Line

120ml Brezhnev-era Московская Special Vodka

3ml Venediktine (yellow)

One drop Elektrichka track oil

Garnish with desiccated black rye bread cube

All this time, we were watching the live feed from the Thiasus control center in Reykjavik. It was, like everything else, a drinking game. Every time another competitor passed out or wound up in the infirmary we raised a toast. The Japanese team discovered the human limits of saké consumption the hard way, but they went out with honor, maintaining good posture throughout the coma. The Batswana broke the madila record (good show!) but didn’t heed the old rule: “Rye before madila, never illa, but madila before rye, goodbye.” And the French. Oh, the French! They just started arguing and forgot to get to the hard stuff. They were found passed out with an empty case of Château Margaux 1787 under a pile of Claude Buffier first editions. Et voilà.

But the Russians were running a hard, hard game. They kept up with us move for move, finally parrying our Moscow to the End of the Line with Vyacheslav’s special variant of the old Baba Yaga. It’s spiced up with fresh human blood, whence the famous scars on his left arm.

The Baba Yaga Vyacheslav

Grease interior of highball glass with rendered chicken fat

75ml vodka (Russian, whatever, who cares?)

30ml Tarasun (genuine Buryat mare’s milk recipe only)

10ml Бальзáм «Крáсная Поля́на» (or the Karelian if you can get it)

Fresh human blood (to taste). Consensual, healthy donor only, please. (The Thiasus is a wholesome, family spectacle and does not condone unsafe activities of any kind.)

Then the Russians got serious. The board lit up with betting when the uncut TS-1 hit their bloodstreams. TS-1 is the preferred jet fuel of Russia and the CIS states, designed for cold-weather flying, and higher volatility than the Jet A-1 we were carrying. That gave them an edge, but we had to keep up.

Kati and I locked eyes and outstripped the Russians six shots to five. Ettore and company gave it a pass, and you should too. Even, arguably, with a gun to your head. I wished I’d had one handy, truth told. Kati cleverly passed out, her SCRAM-2 glowing safely blue.

Suddenly (of course) there was a disturbing round of impact noises. The copilot raced out of the cockpit and announced that the fuel tanks had been pierced and we were losing fuel. And the Sukhoi, incidentally, had flown past us from below.

Things don’t usually go this way in the Thiasus—but then, not everybody can hold their TS-1.

The last thing I remember, I was being hauled into the front section of White Collar. There was a hard clank and a dense, metallic screech. Then we were in free fall.

TO BE CONTINUED