“At first, moving to the countryside from Austin felt like an incredible peace,” says Texas-based poet Derrick C. Brown in a recent interview with PDX Magazine. “And then you begin to notice scorpions, and massive spiders, snakes, vultures and striped hornets.” The prolific poet relocated from his adopted city of Austin to the small country town of Elgin, Texas to write his most recent book, Our Poison Horse, a collection of poetry. His work oscillates from inspiringly personal to unexpectedly humorous. “It is all horror at first,” continues Brown about the critters in his new pastoral setting, “and then you change and you begin to love watching them move. All that slither and nasty becomes fascinating. The book managed to find a lot of humor in it.”

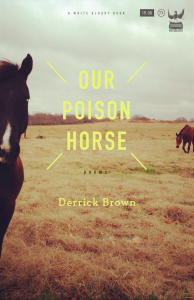

Our Poison Horse, Brown’s fifth book, is widely considered to be a compilation of more intimate and autobiographical poems than his previously published collections. Such revelations were spurred by Brown’s retreat into the countryside, which allowed for singular focus from which subtle details emerged, and unlikely connections were forged. “Every morning, I would quiet down, stare out into the field where we were watching our neighbor’s horse, a horse that was poisoned with pesticide by some local boys, a horse with massive scars all down its body from its skin peeling from the poison sprayed upon it maliciously by some bastard kids,” remarks Brown. “I watched the horse heal and finally come to me, and trust me and eat carrots. Something about that horse, Lacey—about it not trusting me and then warming up—pulled something out of me that I didn’t know I was ready for.”

For close to two decades Brown has crisscrossed the globe, changing people’s perceptions about the importance, accessibility, and relevance of poetry. He achieves this not only by reading his work aloud, but by understanding the reading of his work to be just one part of a larger live experience. Often, his readings have a musical complement. Many of these pieces were created in one weekend with Cottage Grove-based musician Richard Swift, who has lent his talents to the Shins and the Black Keys. According to Brown, the creative and musical weekend was fueled by tequila and fried chicken. “I kept throwing him feelings like a metaphysical weirdo and he kept nailing all the soundtrack material that back me up—and fast,” reveals Brown. Similar sessions occurred with Oregon resident and composer Timmy Straw and New York-based experimental multi-instrumentalist Emily Wells. “I am lucky to use their juice,” is how Brown explains it.

— Mary Locke

Next week Derrick Brown brings his live show to five different stops in the Rose City:

Oct. 11 – Back Fence PDX: Russian Roulette at Disjecta; 8 p.m.; $15 (8371 N Interstate Ave.)

Oct. 12 – Reading at Independent Publishing Resource Center; 7 p.m.; free (1001 SE Division St.)

Oct. 13 – Appearance in Action/Adventure Theater (1050 SE Clinton St.)

Oct. 14 – Reading at Reading Frenzy; 7 p.m.; free (3628 N Mississippi Ave.)

Oct. 16 – Appearance on LiveWire; 7:30 p.m.; $25 (Lincoln Hall at PSU)

Excerpts from Our Poison Horse:

LOUISIANA VS. THE HAIR CLUB FOR MEN

My hair quits and quits every year

and the more it quits

the less love letters you get.

It wanders

towards the silver and black

shower drain.

A lone, daddy long legs spider

slides toward the dark-

I wished him well,

cupped the water and

dumped it on him.

Fuck you, creep.

The worst thing I saw today

was when, at the last moment,

the crook of his leg

reached up

from the hole of the drain

trying to hang on.

Oh God. Me too, I say.

Me too.

I turned up the water

and the sliver of leg

quietly went away.

30 miles of the state of Louisiana

erodes away

every year

and there is no sorrow

to assign to it.

Me too.

TONGUE ON THE WALL

“No one should outlive his power.”

-John Davidson

John Berryman missed

and it aint nothin’.

Wrote down the sickness and long river

showed the world

head as a spinnaker,

constipated force of confessional love,

invincible heavy-

living in the North blue boredom of beauty

dying his way.

A bridge crosses the Mississippi.

Berryman stands upon it.

The bells spoke.

Feet first.

Death beard flipping up

like a tent flap in the breeze.

Jumps.

Misses the water.

Hits the bank.

So he could finally feel dumb?

So we could see you?

So you could suicide note all of us with genius entrails?

Because hard earth is less scary than the dark, forgiving rivers?

Because the soil could push out what you couldn’t?

I write in a library of a remodeled home in Massachusetts

and I don’t know any of the titles on the white shelves.

Surrounded

I feel dumb.

As dumb as last week,

remembering how I felt seeing the first book I ever wrote

in a massive used bookstore

for a dollar.

I wanted to cry. I tried so hard.

I now want to stop, not because someone

abandoned my work, but because

there is just so much

but it aint nothin’.

Someone kissed me once and bruised me good and it ain’t enough

and I know what a snowmobile feels like in mid air and it ain’t enough

and I got lost in sunlight on an island and found unopened wine and it ain’t enough

I have a couple of good dream songs that are my best

and it aint nothin’.

John Berryman’s Dad,

shotgun blasting his tongue onto the wood paneling,

how that photo repeated on every page

the end of language,

the end of Boy.

John are you whispering

you just don’t know.

you just don’t know

yet.

Poetry didn’t take your life.

It kept you here.

It kept you here until you closed your eyes

to the spirits, to the lawns of America,

and grew away from the power of swallowing birds

and the hissing fuels of night.

Did going inside kill you?

I hope you missed.

If you dig at a foundation for too long

the home

will collapse.

Here I write under the shelf

of the books pulled from Goodwill

from dead libraries and

I smile dumb. Is everyone dead?

John, John,

Over-read John.

Being forgotten is not as bad

as hoping you aren’t.

Stillness,

it aint nothin’.

MENDER/ DESTROYER

Cristin and I were chatting

about her break up, her new life

how everything was brand new

and then—

her chair broke

and she fell to the floor

like mashed potatoes.

She didn’t cry.

She just laid there, stretched out

and looked like an extra, waiting

for action to be called in a catastrophe film.

When a poet eats it, they begin sorting out the meaning

of all broken chairs,

of all support

surprising you

and caving in suddenly,

unsure of

what sucks more- the bruise or

having to check chairs for the rest of your life.

I helped her up. Swung open the glass door.

I threw the chair high into the backyard air

and watched it shatter.

“Fuck this chair.

This chair is from the forest of assholes.

This chair can eat my hot fuck and die.”

Cristin then quietly went outside, barefoot

collected the pieces from the grass

and took it into the garage

so she could fix it.

“It didn’t break.

I broke it.”

Give Local Art This Holiday, Part 2 - PDX MagazinePDX Magazine

[…] can read our post on him HERE which includes three poems excerpted from his latest book. Order Our Poison Horse at […]